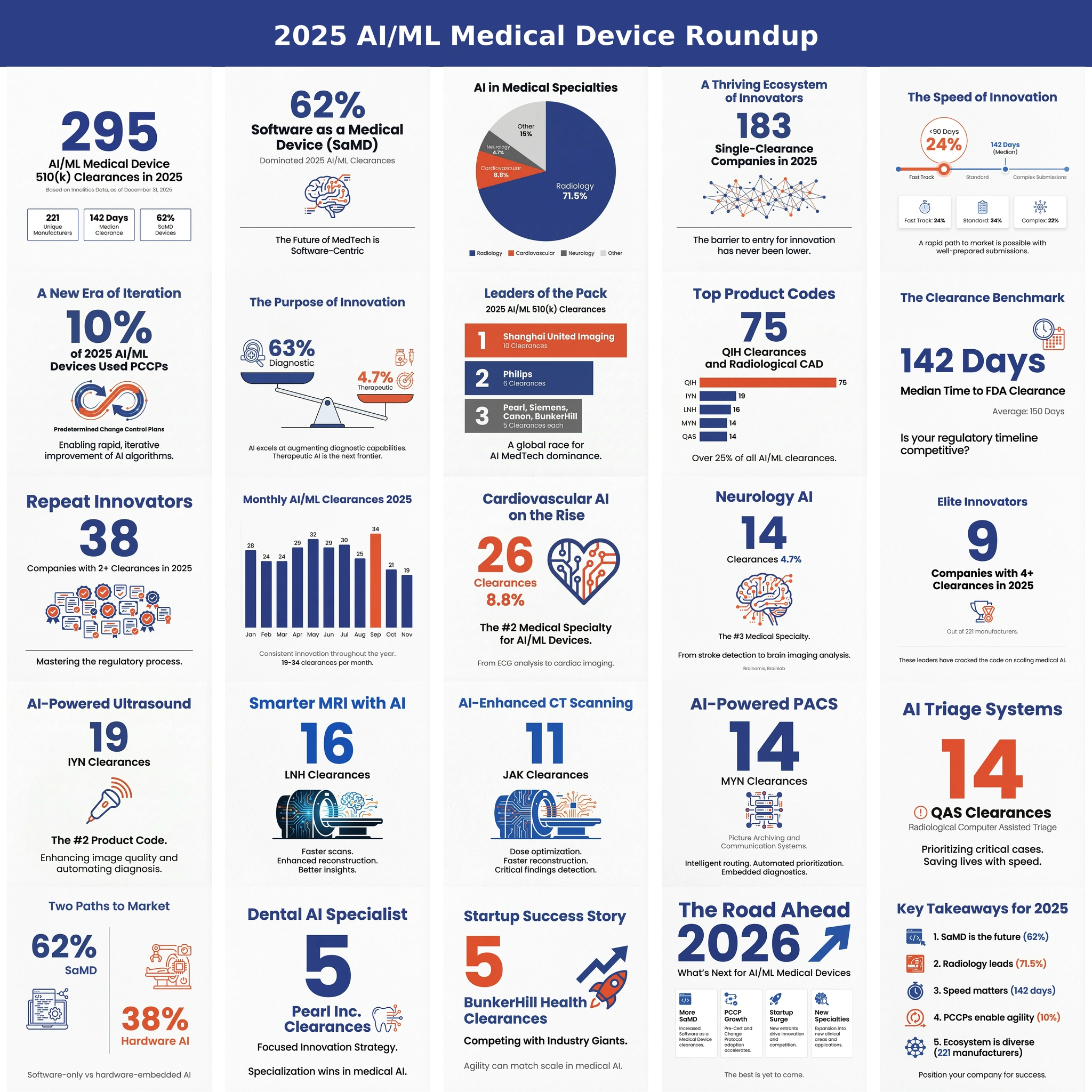

Executive summary 🔗

- This is probably the first of many: K252366 shows the path FDA is rewarding for modern AI, especially foundation-model-like approaches.

- Constrained shell, generalist core: keep the intended use narrow, outputs bounded, and validation tied tightly to what you claim.

- Triage is the start: workflow wins without touching primary diagnosis, which keeps the risk story clean.

- The pattern is repeatable: define a small set of findings, validate, and use a PCCP for controlled improvements.

What K252366 gets right about foundation-model triage 🔗

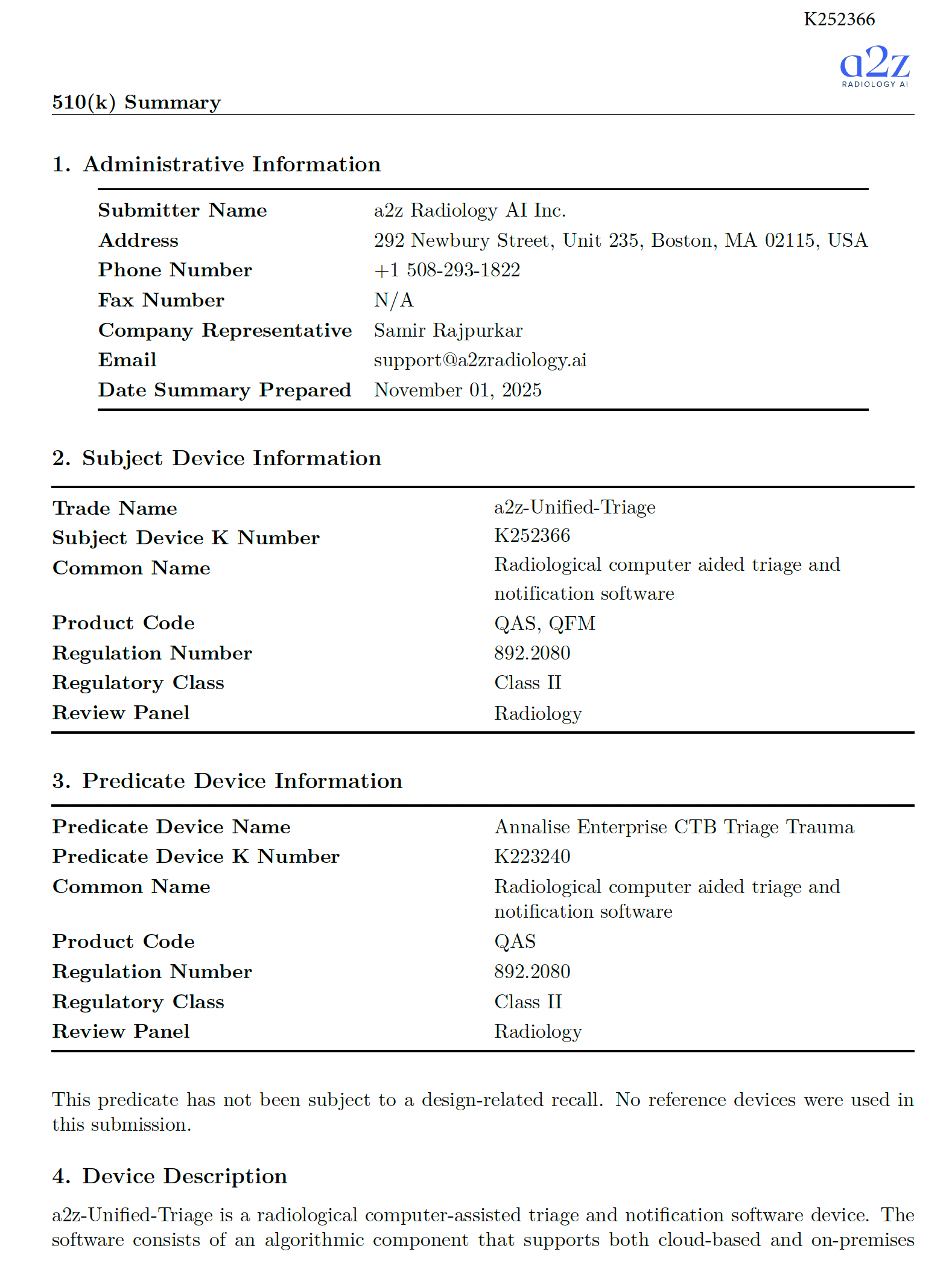

K252366 (a2z-Unified-Triage) is a clean example of how to commercialize modern AI in radiology without trying to boil the ocean on day one.

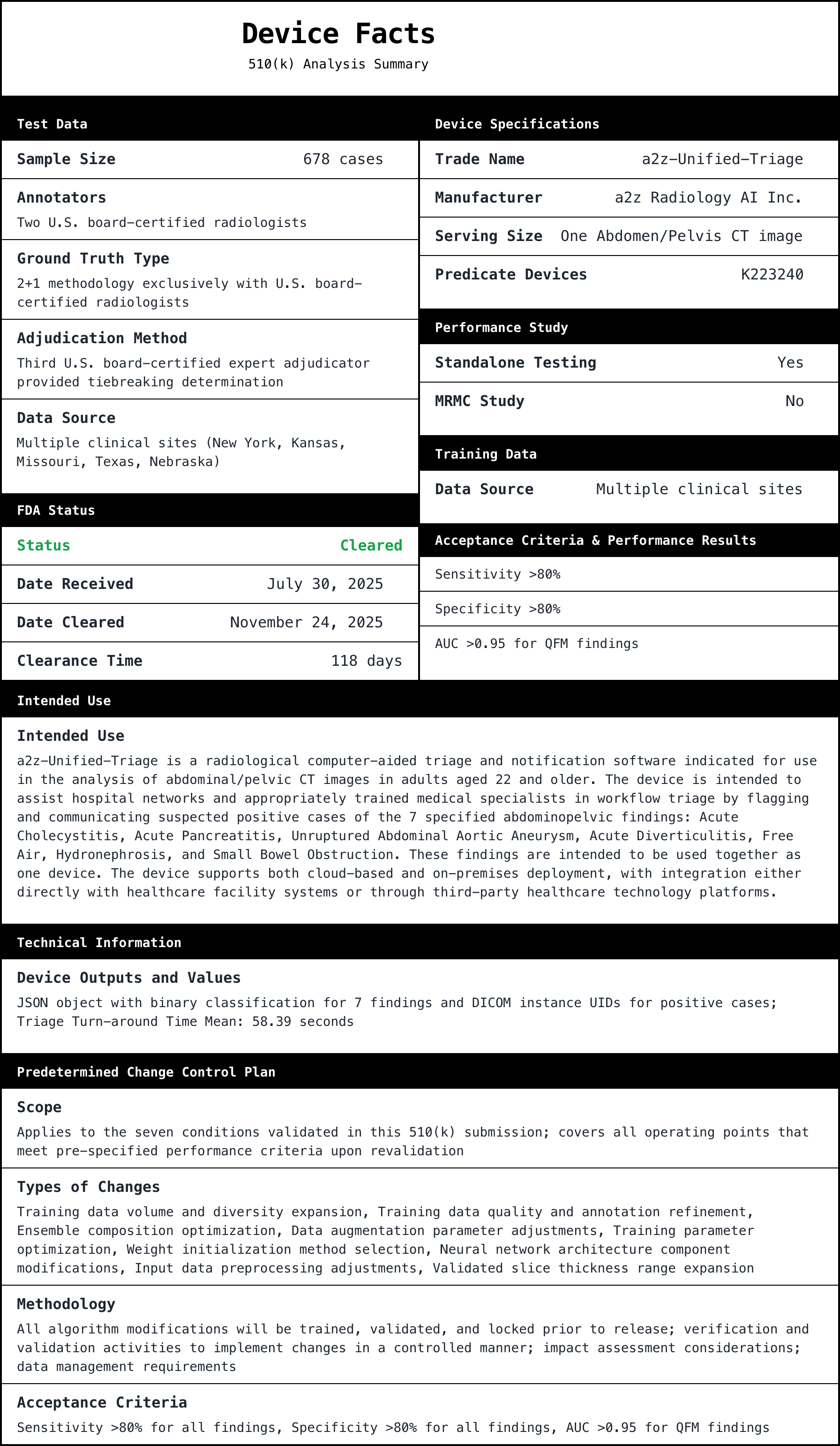

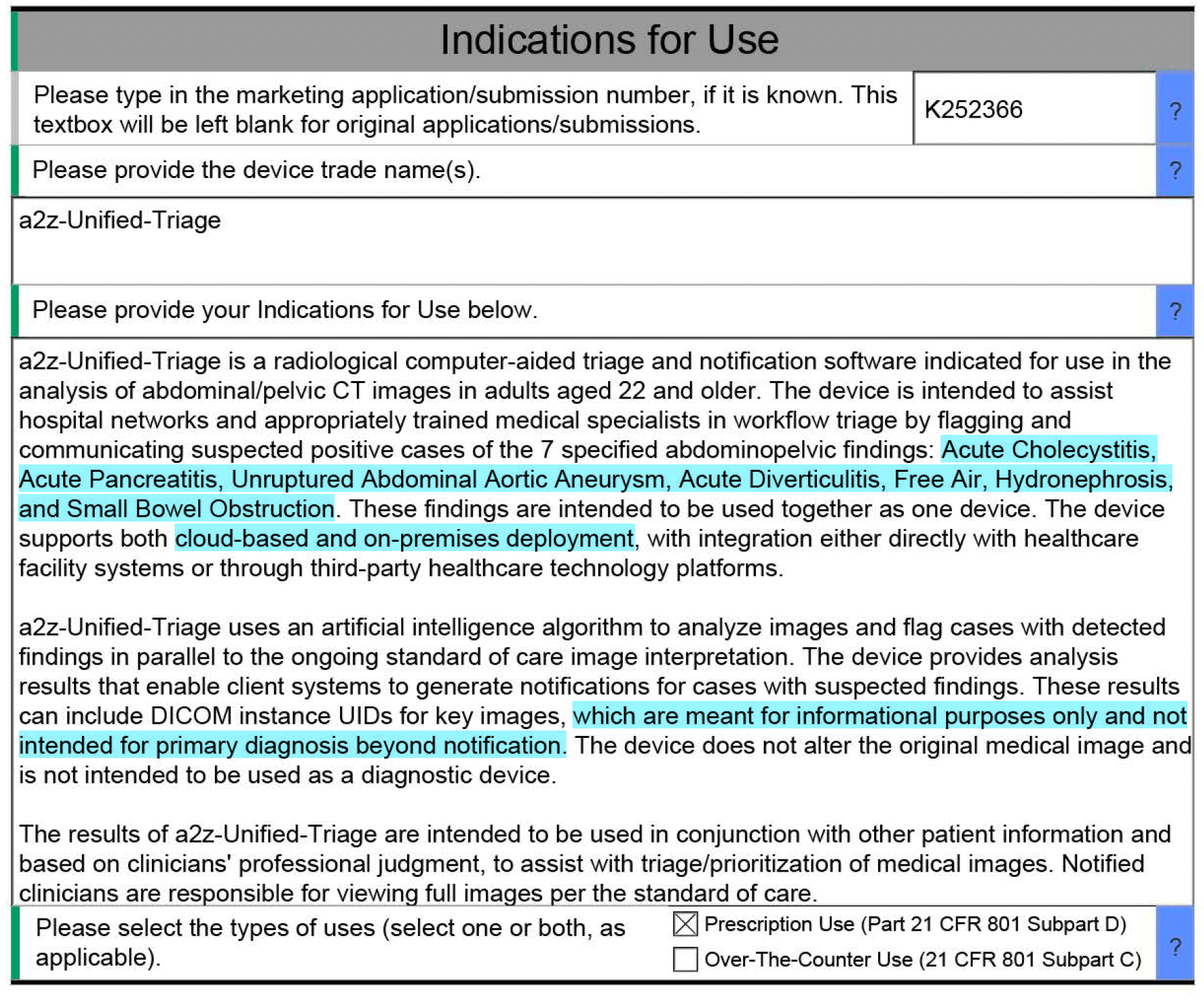

The device is a radiological computer-aided triage and notification product under 21 CFR 892.2080 (Class II). It processes abdominal/pelvic CT studies for adults 22+, runs in parallel to standard of care, and returns results to a client system for worklist prioritization and notifications.

A small but telling detail: it explicitly says it does not alter the original image and is not intended to be used as a diagnostic device. That framing matters. It keeps the core risk story coherent.

I remember a radiologist once joking that triage AI is the only software that helps even when you ignore it. That's basically the point: it nudges workflow, not interpretation.

Computer-aided triage is a very deliberate claim 🔗

"Triage and notification" sounds modest, but it's strategic. A triage tool:

- Runs in parallel to the reading workflow.

- Prioritizes which cases get attention sooner.

- Avoids claiming that the software is the "reader."

That last bit is the regulatory difference between "assist workflow" and "replace clinical judgment." The summary also emphasizes that the device does not remove cases from the standard care reading queue and does not de-prioritize cases. That's another deliberate boundary.

Seven predefined findings: the guard-railed shell approach 🔗

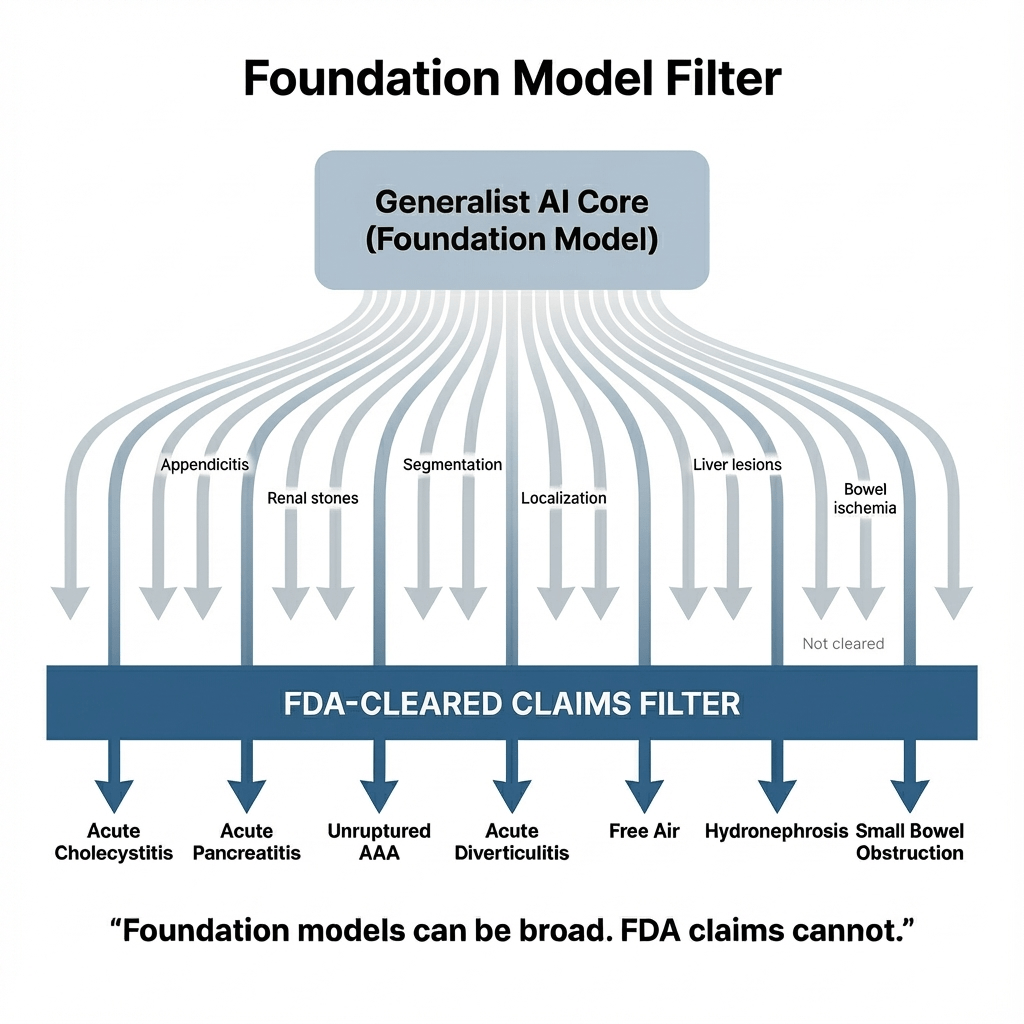

This submission is also a case study in how to productize a likely generalist model.

Even if the underlying model family could detect far more than what's in the label, the cleared device starts with seven specific findings. That's the right pattern:

- A generalist core (foundation-model-like capabilities).

- A constrained "shell" with clear claims, bounded outputs, and defined validation.

The labeling and validation scope then stays crisp. That makes it easier to defend performance, safety, and post-market monitoring.

What exactly is being claimed and how it was tested 🔗

Below is the core factual payload from the 510(k) summary: the findings, the study size, the acceptance criteria, and observed values.

| Finding | Product code bucket | Acceptance criteria stated in summary | Test dataset (analytic) | Positive cases (prevalence) | Observed performance (examples of operating points) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

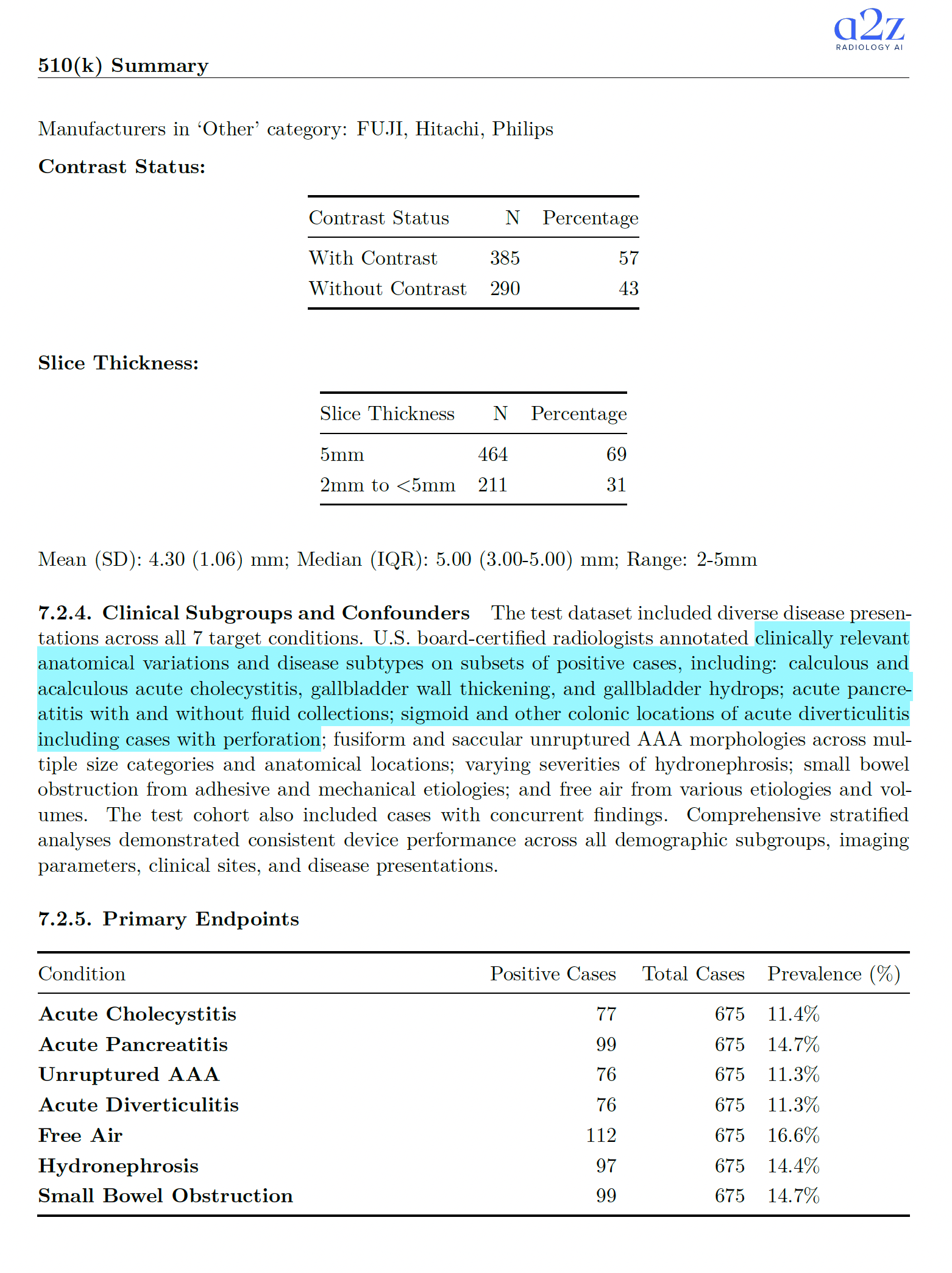

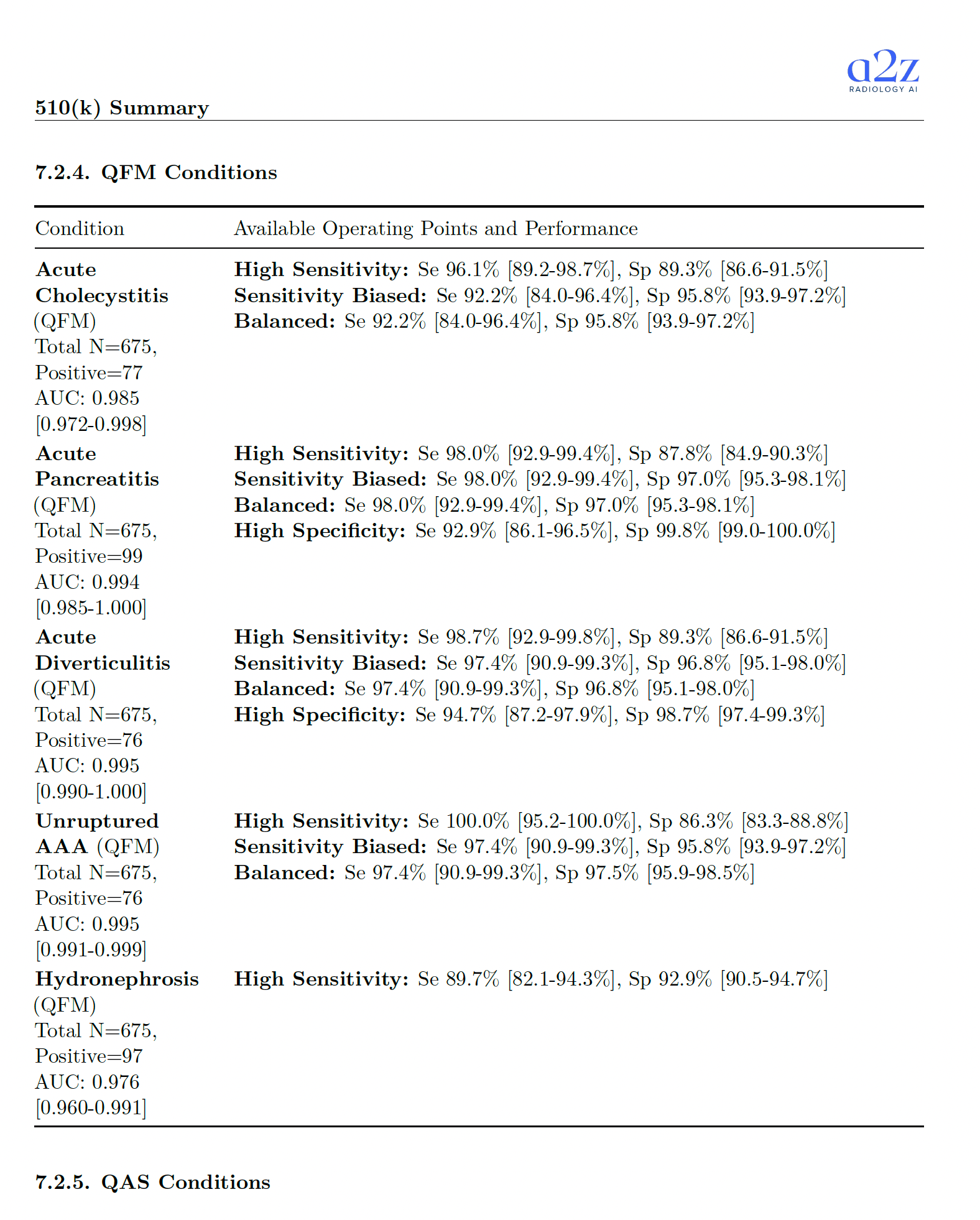

| Acute Cholecystitis | QFM | AUC > 0.95 | N=675 | 77 (11.4%) | AUC 0.985 [0.972-0.998]; High Sens: Se 96.1%, Sp 89.3%; Balanced: Se 92.2%, Sp 95.8% |

| Acute Pancreatitis | QFM | AUC > 0.95 | N=675 | 99 (14.7%) | AUC 0.994 [0.985-1.000]; High Sens: Se 98.0%, Sp 87.8%; Balanced: Se 98.0%, Sp 97.0%; High Spec: Se 92.9%, Sp 99.8% |

| Unruptured Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm | QFM | AUC > 0.95 | N=675 | 76 (11.3%) | AUC 0.995 [0.991-0.999]; High Sens: Se 100.0%, Sp 86.3%; Balanced: Se 97.4%, Sp 97.5% |

| Acute Diverticulitis | QFM | AUC > 0.95 | N=675 | 76 (11.3%) | AUC 0.995 [0.990-1.000]; High Sens: Se 98.7%, Sp 89.3%; Balanced: Se 97.4%, Sp 96.8%; High Spec: Se 94.7%, Sp 98.7% |

| Hydronephrosis | QFM | AUC > 0.95 | N=675 | 97 (14.4%) | AUC 0.976 [0.960-0.991]; High Sens: Se 89.7%, Sp 92.9% |

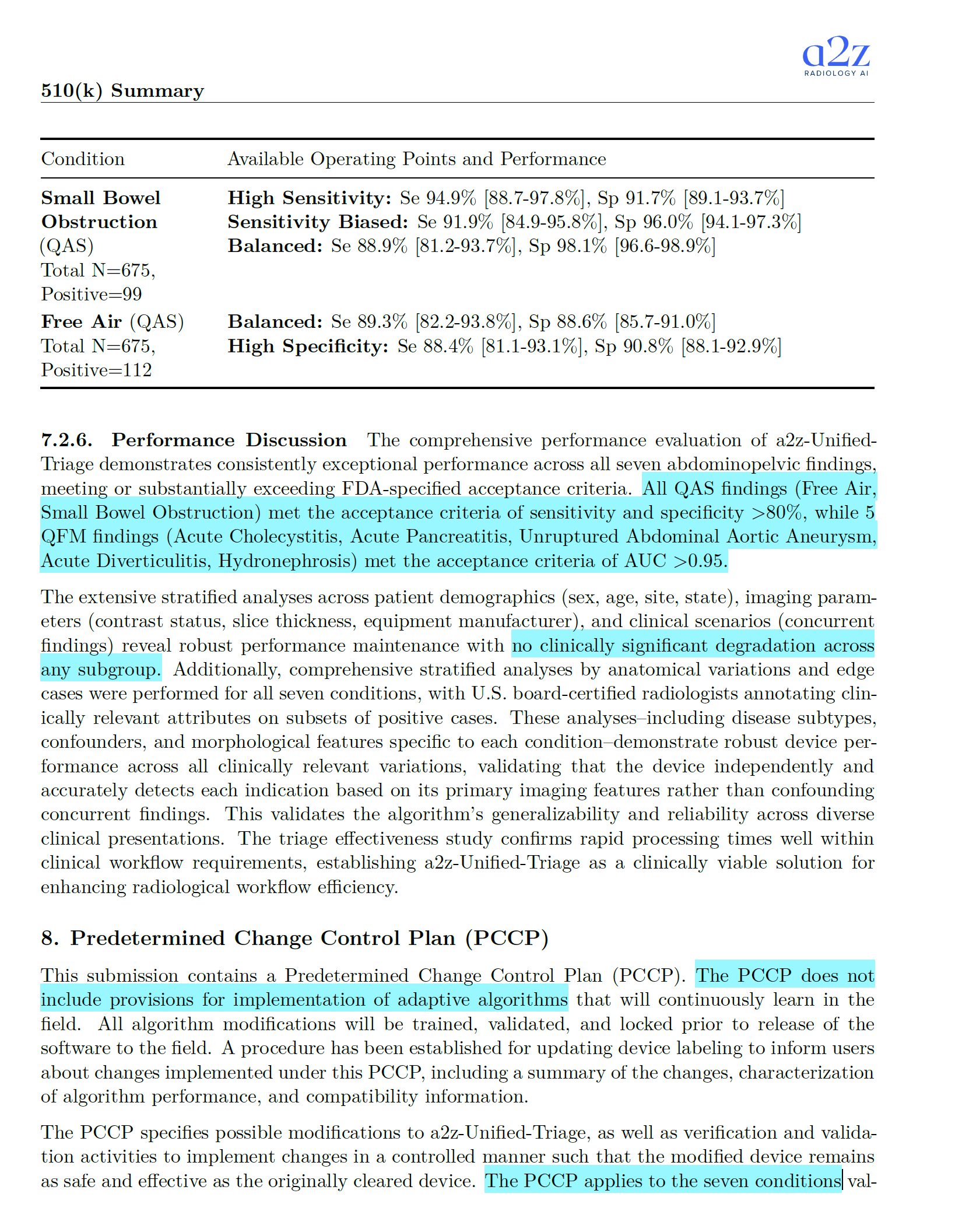

| Free Air | QAS | Se > 0.80 and Sp > 0.80 | N=675 | 112 (16.6%) | Balanced: Se 89.3%, Sp 88.6%; High Spec: Se 88.4%, Sp 90.8% |

| Small Bowel Obstruction | QAS | Se > 0.80 and Sp > 0.80 | N=675 | 99 (14.7%) | High Sens: Se 94.9%, Sp 91.7%; Balanced: Se 88.9%, Sp 98.1% |

Study and test data details (from the summary):

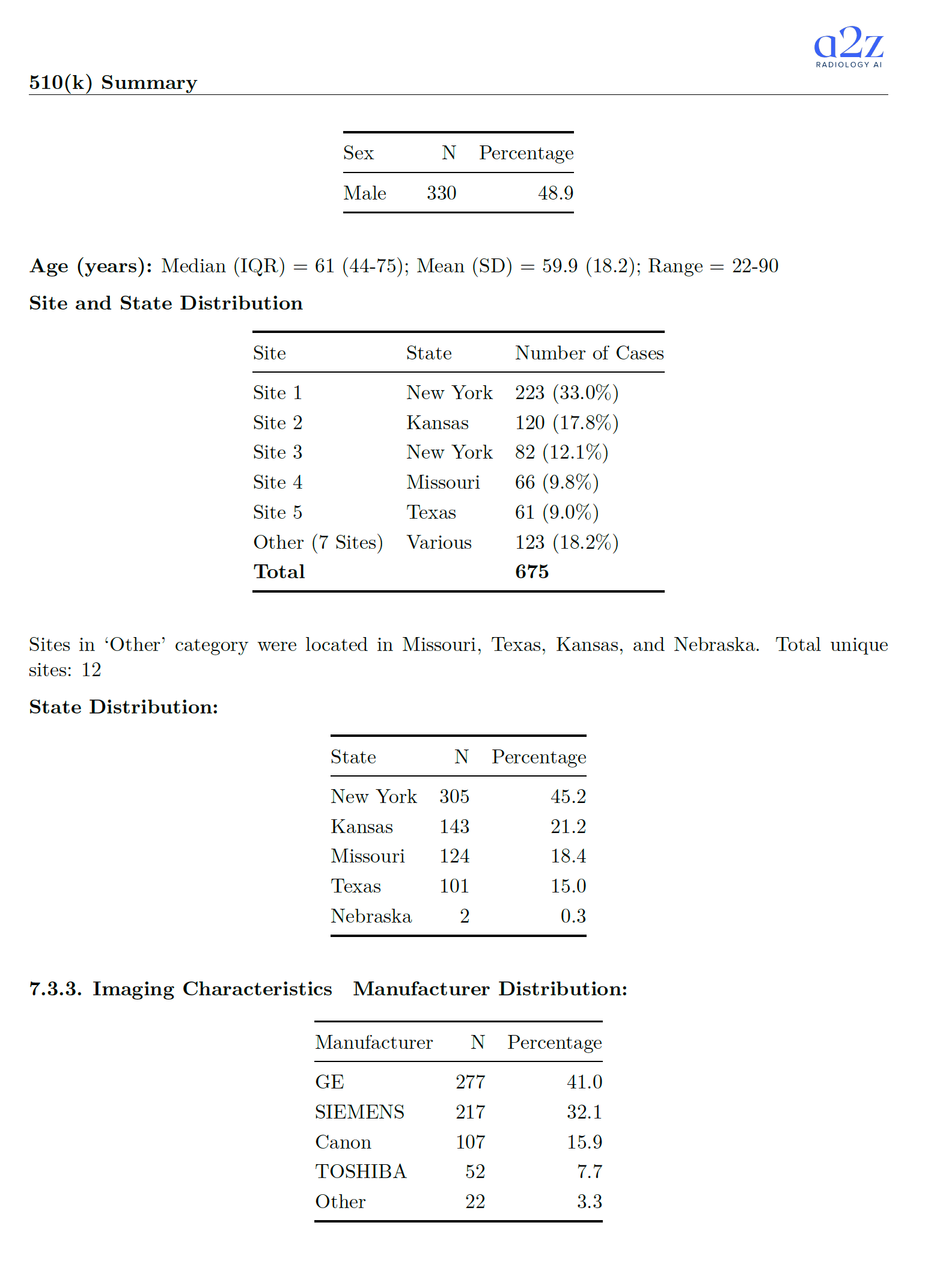

- Test cohort started at 678 cases, with 3 excluded during inference QC. Final analytic cohort: 675 cases from 643 unique patients.

- Ground truth used a 2+1 approach with U.S. board-certified radiologists (two independent reads plus adjudication on discordance).

- Data came from 12 sites across multiple states. Manufacturer mix included GE, Siemens, Canon, Toshiba, and "Other." Studies included both contrast and non-contrast, with slice thickness 2-5 mm.

Why triage is often simpler to validate (and why that matters for foundation models) 🔗

Triage devices still need serious validation, but they're structurally easier to defend than "interpretation-changing" systems.

Here's the key point: triage software does not change what the radiologist sees. It changes when a case gets looked at.

That usually means:

- Lower risk than tools that annotate, measure, segment, or directly influence the primary diagnostic act.

- Less exposure to automation bias and confirmation bias compared to systems that place boxes on images or present confident-looking localized overlays.

It also changes what kinds of clinical studies are necessary. If the product is not making or modifying diagnostic conclusions, you can often validate with standalone performance against a reference standard, plus workflow-oriented evidence, rather than jumping straight to complex reader-impact designs.

This is likely the early playbook for many foundation-model developers: start with guard-railed triage claims, then expand cautiously, using post-market evidence and better characterization of failure modes to support higher-impact indications.

Also: foundation models today are often better at classification than precise segmentation. Triage leans into that reality. The exact pixel-level location is less important than the likelihood that "something is there," so the workflow can be prioritized.

"Doesn't remove from standard of care" is a risk-management anchor 🔗

The summary explicitly says neither the subject nor predicate removes cases from standard care queues or de-prioritizes cases.

That sentence is doing a lot of work.

- Removing cases is a much more direct clinical intervention.

- It increases the chance that a miss becomes a missed diagnosis.

- It tends to push regulatory risk and study burden upward.

Keeping the human in the loop is what keeps the overall story credible.

The "no UI" pattern reduces validation and security surface area 🔗

The summary reads like a back-end service: it accepts DICOM, runs inference, and returns a JSON result to a client system.

If the device truly has no clinician-facing UI, that's not just a product decision.

- It keeps deployments more general-purpose across sites and IT stacks.

- It reduces the software surface that must be verified and validated.

- It simplifies cybersecurity threat modeling, because you avoid a big set of UI-driven flows, permission states, and user interaction paths.

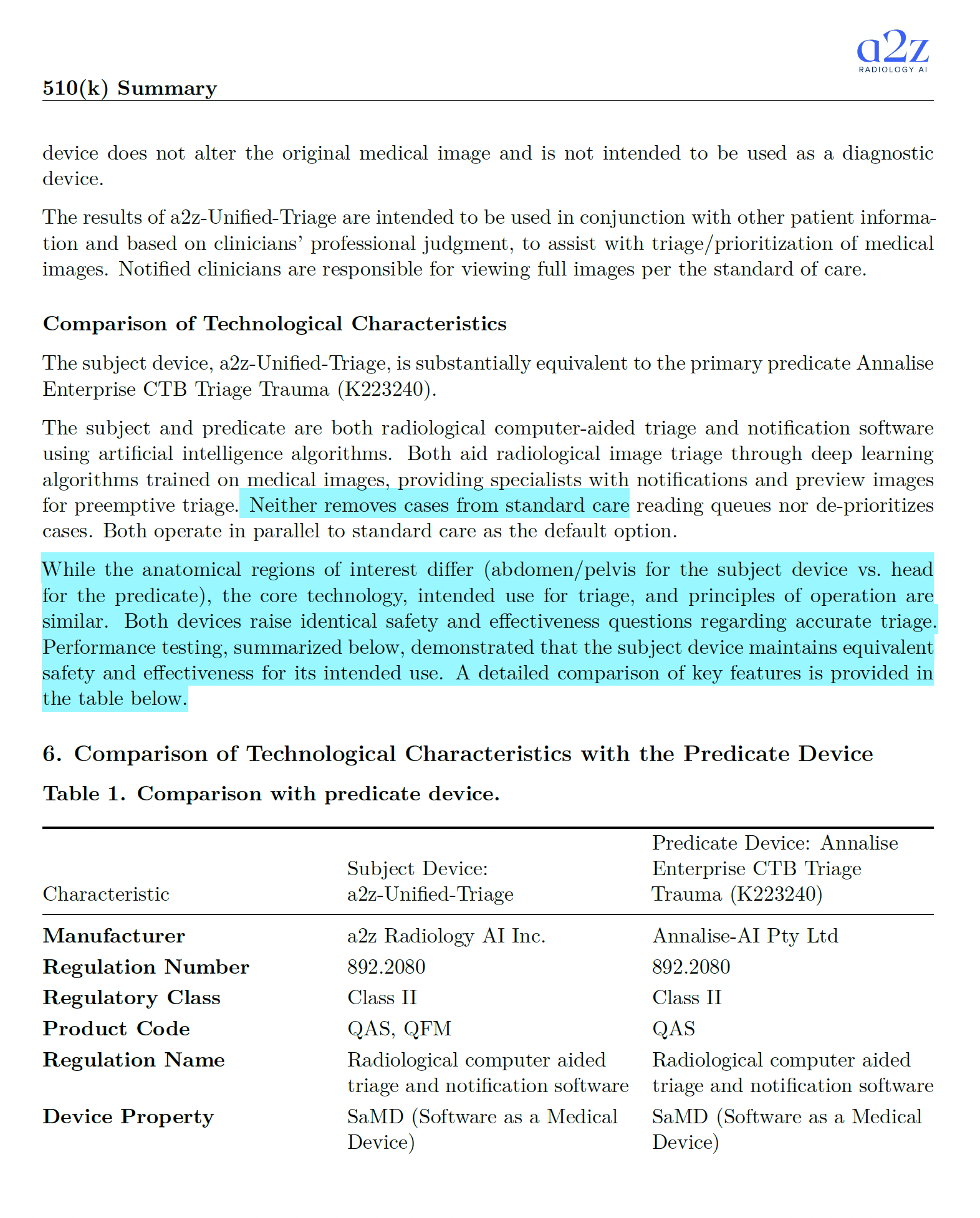

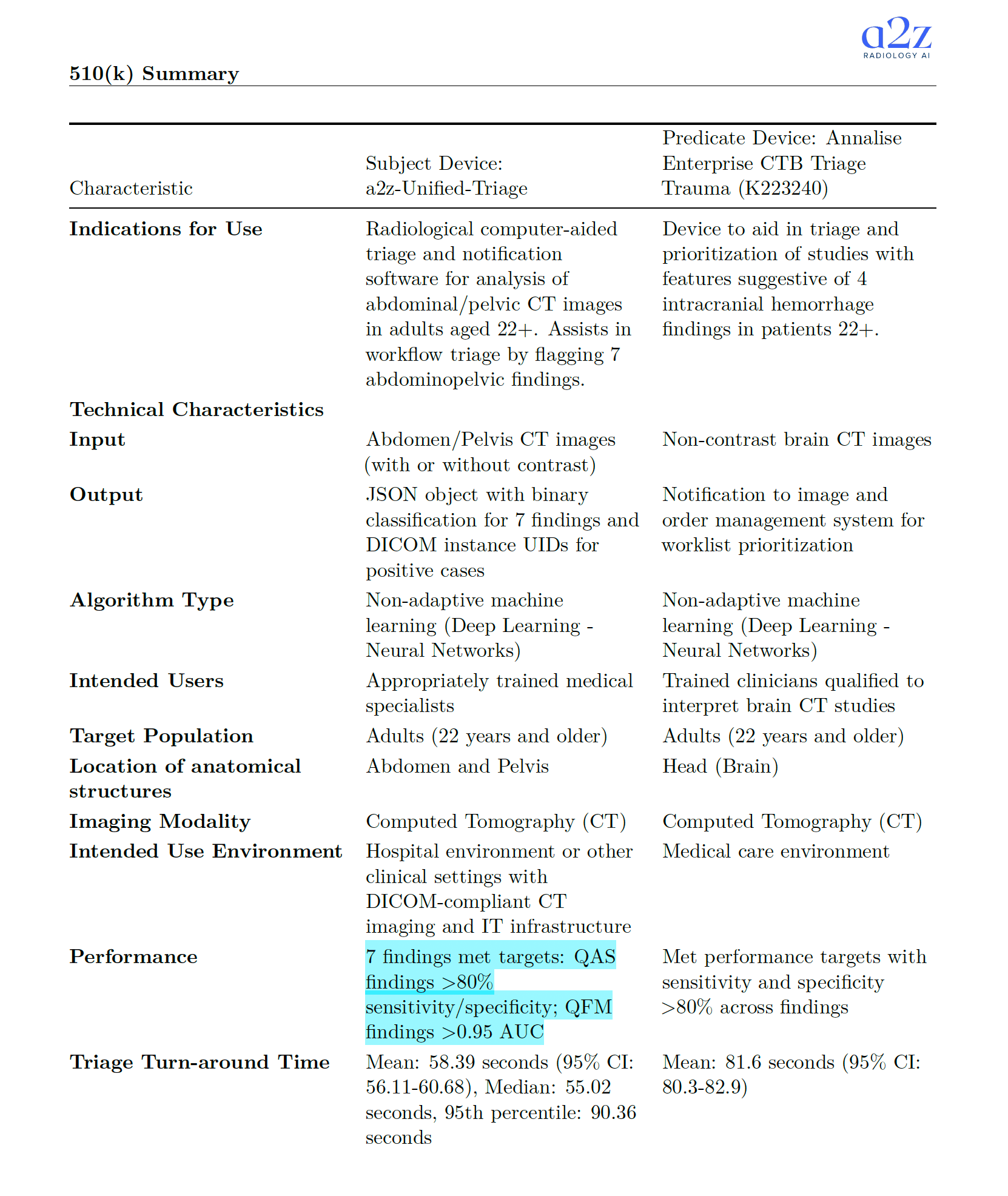

Predicate mismatch in anatomy doesn't automatically break substantial equivalence 🔗

The predicate is Annalise Enterprise CTB Triage Trauma (K223240), which operates on head CT, while the subject device operates on abdomen/pelvis CT.

On first read, that feels like a mismatch. But the core intended use and technology line up: both are AI triage/notification software under the same regulation number.

This pattern has shown up more than once: body part changes do not necessarily invalidate substantial equivalence when the key questions of safety and effectiveness are the same and are addressed with appropriate performance testing.

Acceptance criteria matched to the predicate: do it whenever you can 🔗

The acceptance thresholds in the summary are consistent with what you often see for triage predicates:

- QAS: sensitivity and specificity above 0.80.

- QFM: AUC above 0.95.

Matching your predicate's performance bar is usually the best move. It gives reviewers an apples-to-apples anchor and reduces argument surface area.

"Rough location" vs "specific location": draw the line carefully 🔗

The device can return DICOM instance UIDs for key images. The summary frames these as "informational only," with no markings and not intended for primary diagnosis beyond notification.

This is a common boundary for triage tools:

- Allow a "go look here" pointer.

- Avoid deterministic-looking overlays that imply diagnostic localization.

Other products have learned the hard way that "triage" becomes a much harder sell when you start behaving like a diagnostic locator.

One thing we cannot tell from the summary: whether the manufacturer framed this restriction proactively, or whether FDA pushed for it during interactive review.

675 cases from 643 patients: a small but important nuance 🔗

The summary notes multiple cases per patient for some patients.

That can be totally reasonable, but it matters for statistical independence assumptions and how you think about generalization. It's the kind of line reviewers will notice if anything else feels off.

It never says "foundation model," but you can see the fingerprints 🔗

The summary does not use the phrase "foundation model." Still, the training and validation descriptions emphasize:

- Multiple sites.

- Diverse imaging characteristics.

- Wide patient demographics.

- Strict separation between development and test patients.

That's the kind of language you expect when the underlying model is designed to generalize broadly, and the team wants to show it.

Turnaround time is stated, but it's rarely the gate 🔗

The mean turnaround time is reported as ~58 seconds (with a 95th percentile around 90 seconds).

That's helpful for workflow plausibility, but it's rarely the primary acceptance gate. A fast wrong answer is still wrong. The real question is whether prioritization is accurate enough to improve workflow without creating new harm.

2+1 ground truth looks like the default standard now 🔗

The "two readers plus adjudication" structure shows up everywhere in these submissions for a reason.

- It's practical.

- It reduces single-reader idiosyncrasy.

- It gives you a defendable reference standard without turning the whole study into a reader-performance spectacle.

For triage, it's an especially clean fit.

Confounders and subgroup analysis: how you show you didn't win by accident 🔗

The summary emphasizes stratified analyses across demographics, sites, scanner manufacturers, contrast status, slice thickness, and disease presentations.

That's the correct posture. If performance only looks good in aggregate, reviewers will suspect confounding. If it's consistent across meaningful subgroups, the story holds together.

PCCP: improvement, not expansion of indications 🔗

The PCCP is arguably the most forward-looking part of the package.

Notably, it's scoped to model and process improvements, not "we'll add new indications later." That boundary is sensible. Adding indications changes the intended use story and likely exceeds what a PCCP should cover.

The planned modifications listed include things like:

- Expanding and refining training data.

- Optimizing ensembles and training parameters.

- Adjusting preprocessing.

- Expanding validated slice thickness range.

If foundation-model-driven products are going to ship updates safely, this type of PCCP will become a common pattern: bounded change, pre-specified validation, and documented labeling updates.

Conclusion 🔗

This is probably the first of many. You can already see the shape of how "foundation-model-like" systems will get regulated: a constrained shell around a generalist core.

K252366 reads like a validation of the playbook. Keep the intended use tight. Keep outputs bounded. Prove performance on a defined dataset. Treat workflow impact as the value, and keep primary diagnosis clearly out of scope.

If you're building an AI product and want a clearance path that feels defensible on paper and practical in the real world, start here.

If you want to predicate off K252366, or you have an AI/ML-based device and you want guaranteed FDA clearance and a submission in as little as three months, reach out today.