Two updated FDA guidances landed on January 6, 2026: Clinical Decision Support (CDS) Software and General Wellness: Policy for Low Risk Devices. If you’ve been watching industry commentary, you’d think the agency redrew the entire digital health map overnight. I don’t see it that way. Most of what’s “new” is FDA tightening definitions, adding calibration examples, and making their long-standing risk posture easier to apply. There are a couple of places where policy actually moved, but not nearly as much as the hype suggests.

What follows is a practical comparison of the two guidances, grounded in the “spirit” behind them, with concrete examples (LLMs, chatbots, wearables), tough edge cases, and a set of FAQs you can hand to a product team.

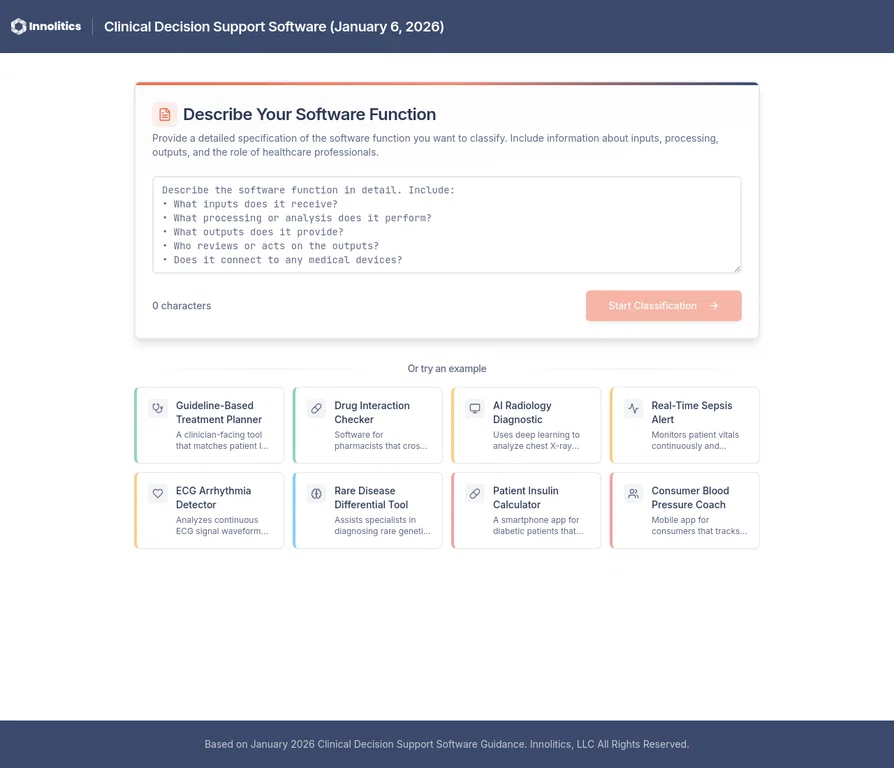

Interactive Assessment 🔗

We built an interactive CDS assessment tool to help you determine whether your software falls under FDA's Non-Device CDS enforcement discretion or requires regulatory submission.

Clarifications and Updates 🔗

Here are some notable changes between the previous and 2026 guidance and what they mean for your device.

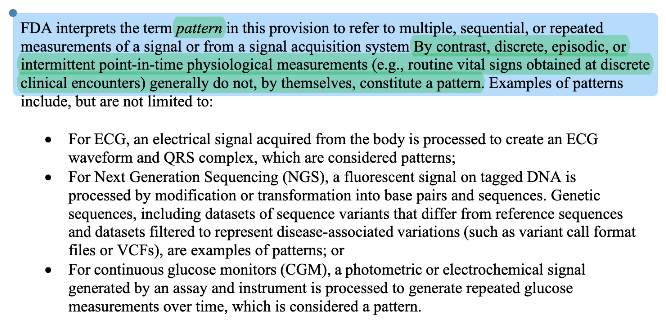

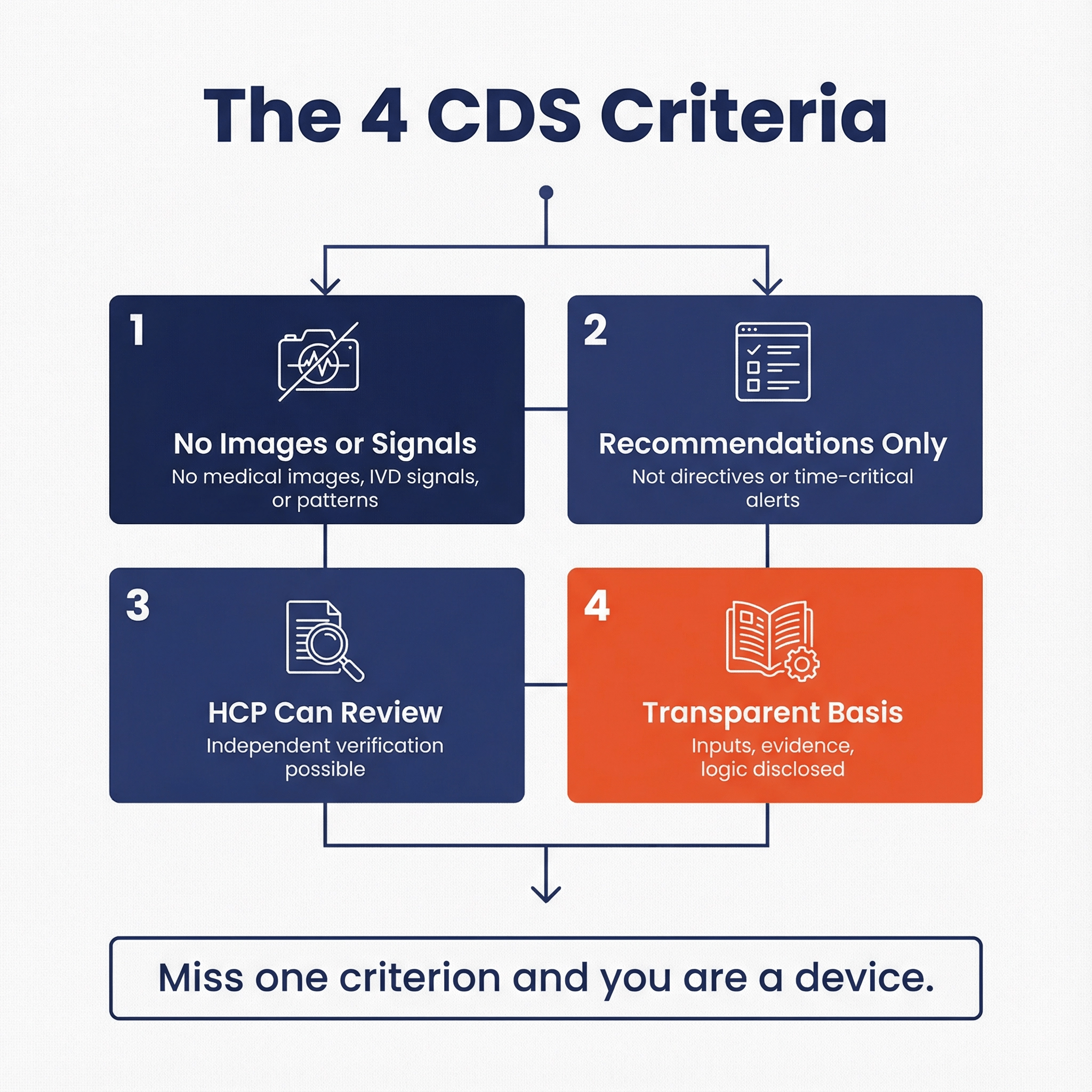

“Pattern” got clarified, not reinvented. 2026 adds explicit language that discrete/episodic/intermittent point-in-time measurements generally don’t constitute a pattern by themselves. That’s FDA clarifying how they already think about risk and signal-processing.

Takeaway: Long term low frequency measurements no longer disqualifies criterion 1.

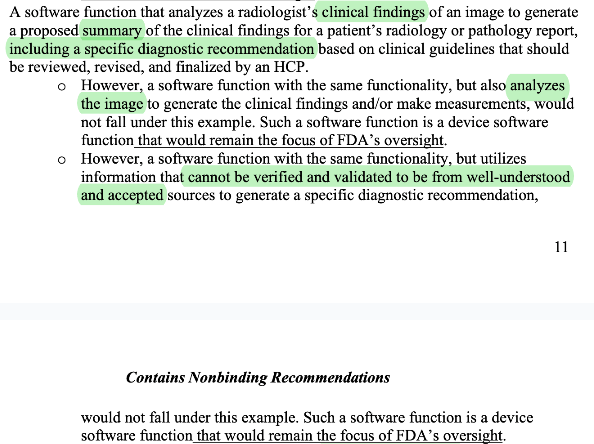

Clarifies that radiology impression generation and summarization of text reports pass criteria 2. This adds much needed clarity that summarization and impression generation tools are not disqualified from criteria 2, potentially opening the door for more advanced LLM powered (jury is still out if that passes criteria 4) tools.

CDS enforcement discretion for “one clinically appropriate option.” Historically, “specific output/directive” was the bright line. In 2026, FDA says if only one option is clinically appropriate and the function otherwise meets all CDS criteria, FDA intends to exercise enforcement discretion. I think this indicates a shift in mindset from the paternalistic approach at FDA before to a more physician autonomy centered one.

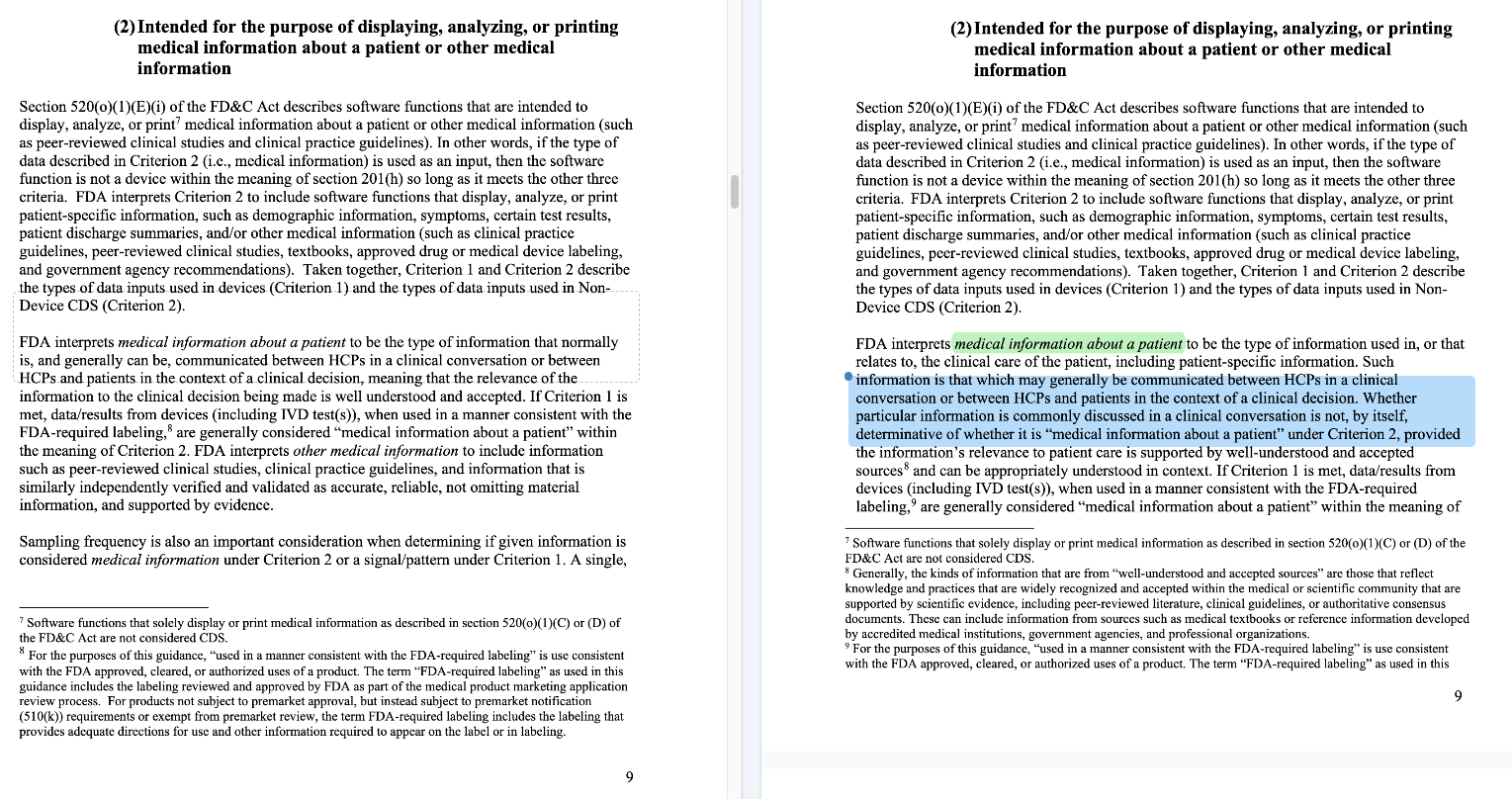

FDA clarified what “medical information” means. It used to mean information only communicable via “clinical conversation” only but they clarified their “spirit” of the guidance to mean “well-understood and accepted sources”. This is likely due to confusion around the original rule. People probably over-fitted to FDA’s guidance to mean only information exchanged verbally in conversation applies. I think this expansion actually opens the door for a lot of applications that transform “medical information” into other “medical information”. When you read the examples, “medical information” now includes things like treatment recommendations, specific diagnosis, and other clinical directives.

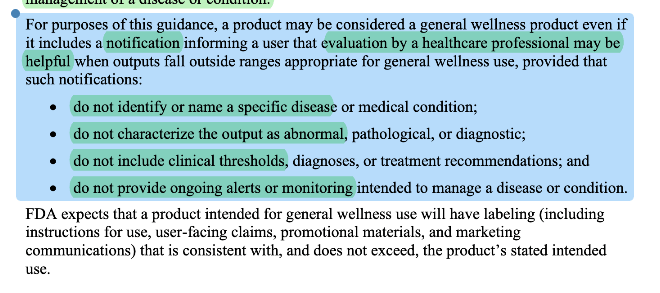

FDA clarified what a general wellness “notification” means. Notifications could still be considered general wellness but there are significant limitations of what you can say about the notification. This does NOT mean that Apple’s hypertension notification feature is a general wellness indication.

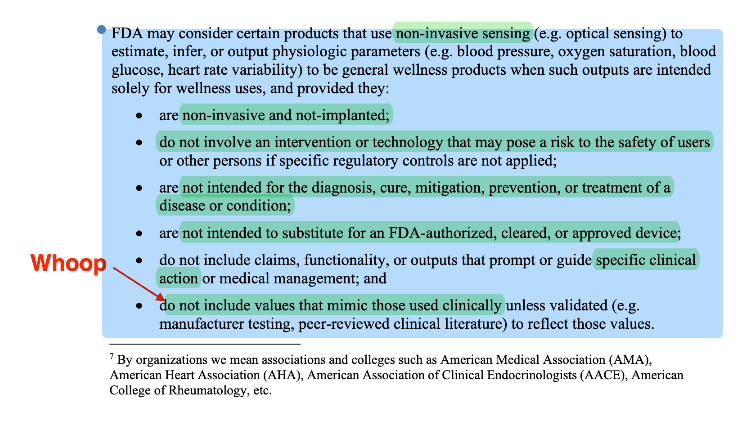

Wellness explicitly addresses non-invasive sensing outputs of physiologic parameters. 2026 adds a structured “may consider” pathway for non-invasive sensing that estimates outputs like blood pressure, oxygen saturation, blood glucose, HRV, when used solely for wellness and with guardrails. However, note that there are quite a few qualification that significantly waters down what you can do with the non-invasive sensing outputs.

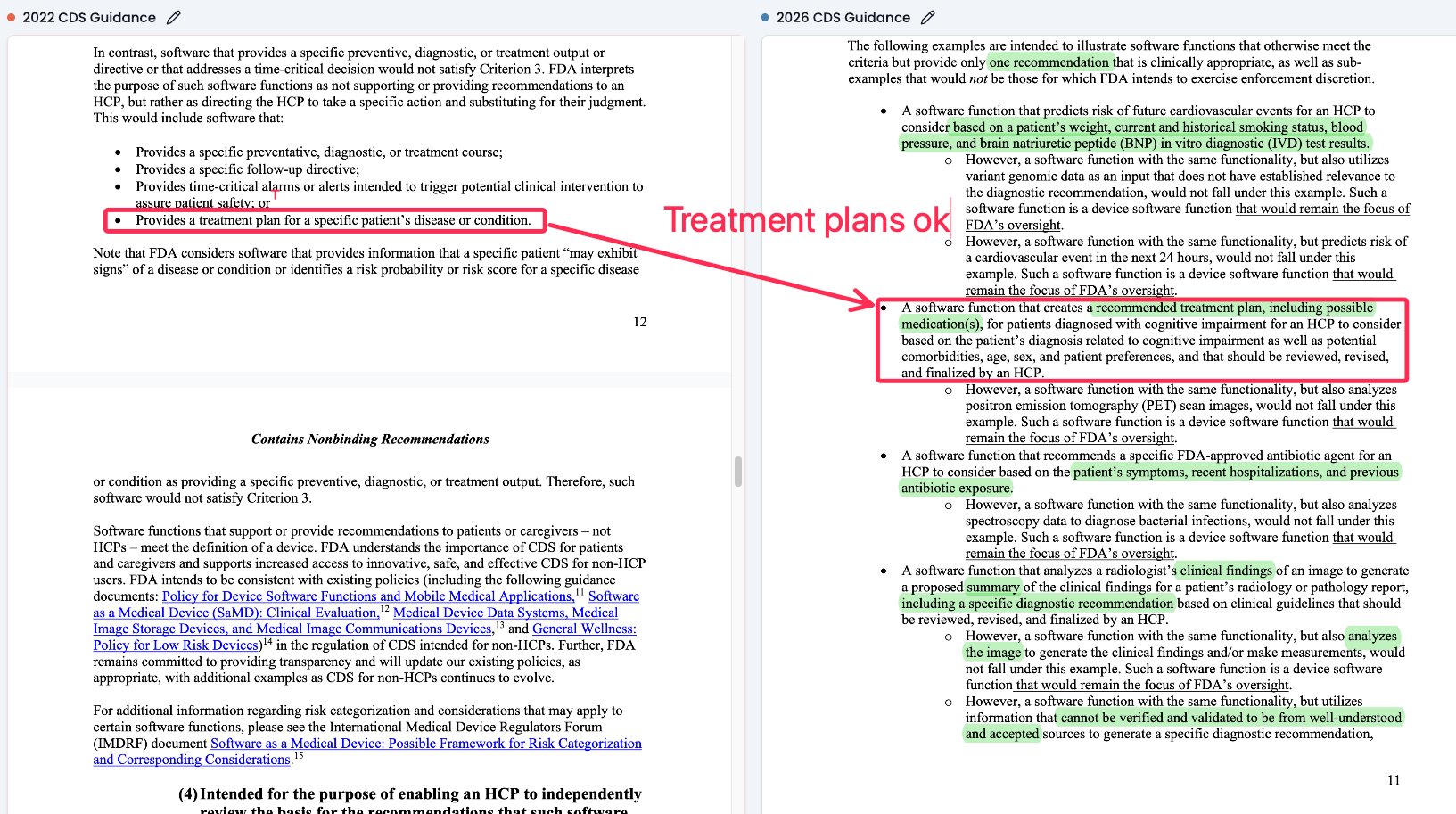

Treatment plans recommendations are now considered “verifiable medical information”. The 2022 guidance gave this a hard no but the 2026 entertains the option as long as a physician reviews it.

Side By Side Diff of the General Wellness Guidance 🔗

Below is a side by side difference between the current and previous version of the general wellness guidance.

Side By Side Diff of the Clinical Decision Support Guidance 🔗

Below is a side by side difference between the current and previous version of the clinical decision support guidance.

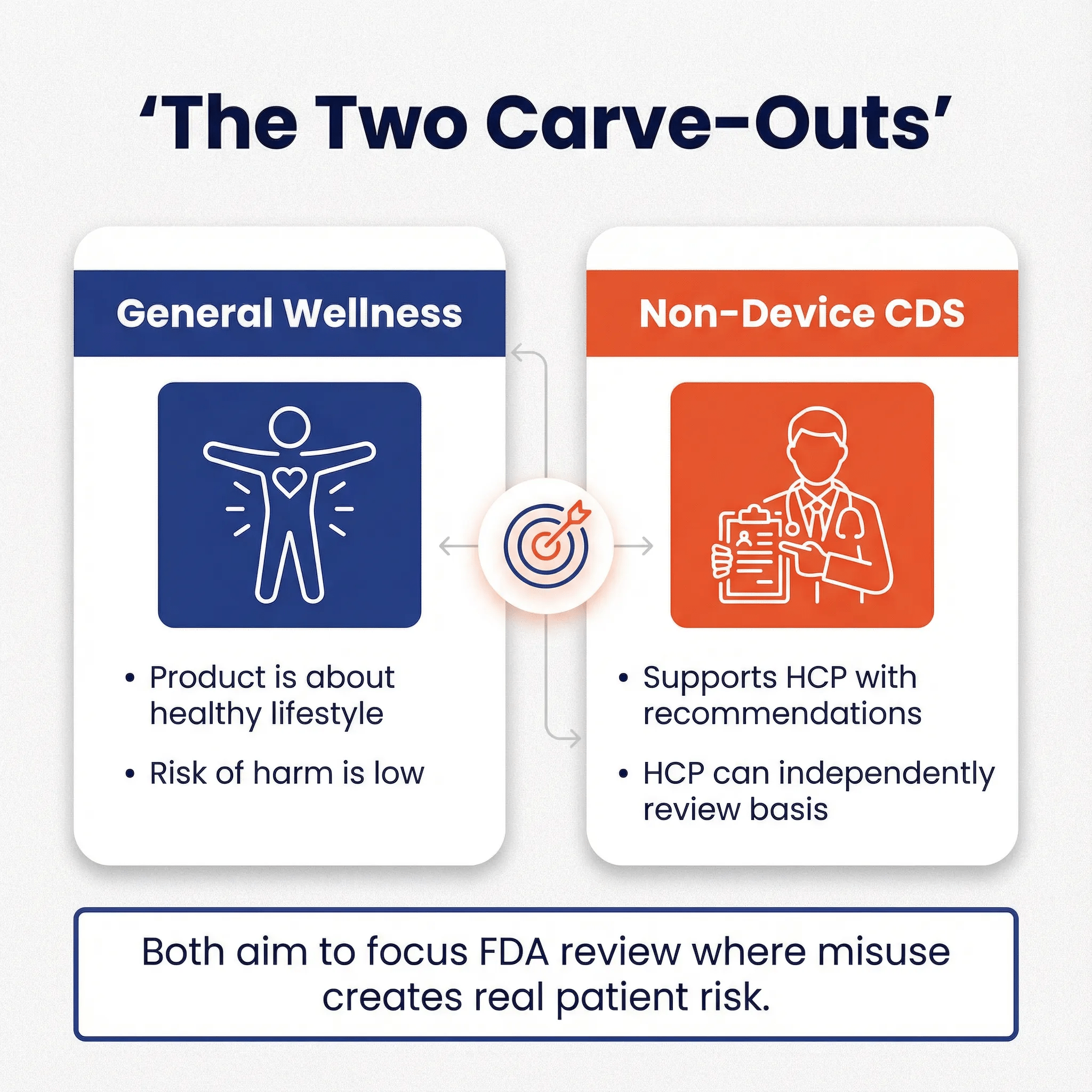

The Two Carve-Outs in One Sentence Each 🔗

General Wellness (GW): FDA largely steps back when a product is about healthy lifestyle or general health, and the risk of harm from being wrong is low.

Non-Device CDS: FDA steps back when software supports an HCP with recommendations and the HCP can independently review the basis, with guardrails around inputs (no images/signals/patterns), time-criticality, and automation bias.

These are different policy tools aimed at the same regulatory goal: spend FDA review bandwidth where misunderstanding or misuse creates meaningful patient risk.

Why FDA Exists, and Why These Carve-Outs Exist 🔗

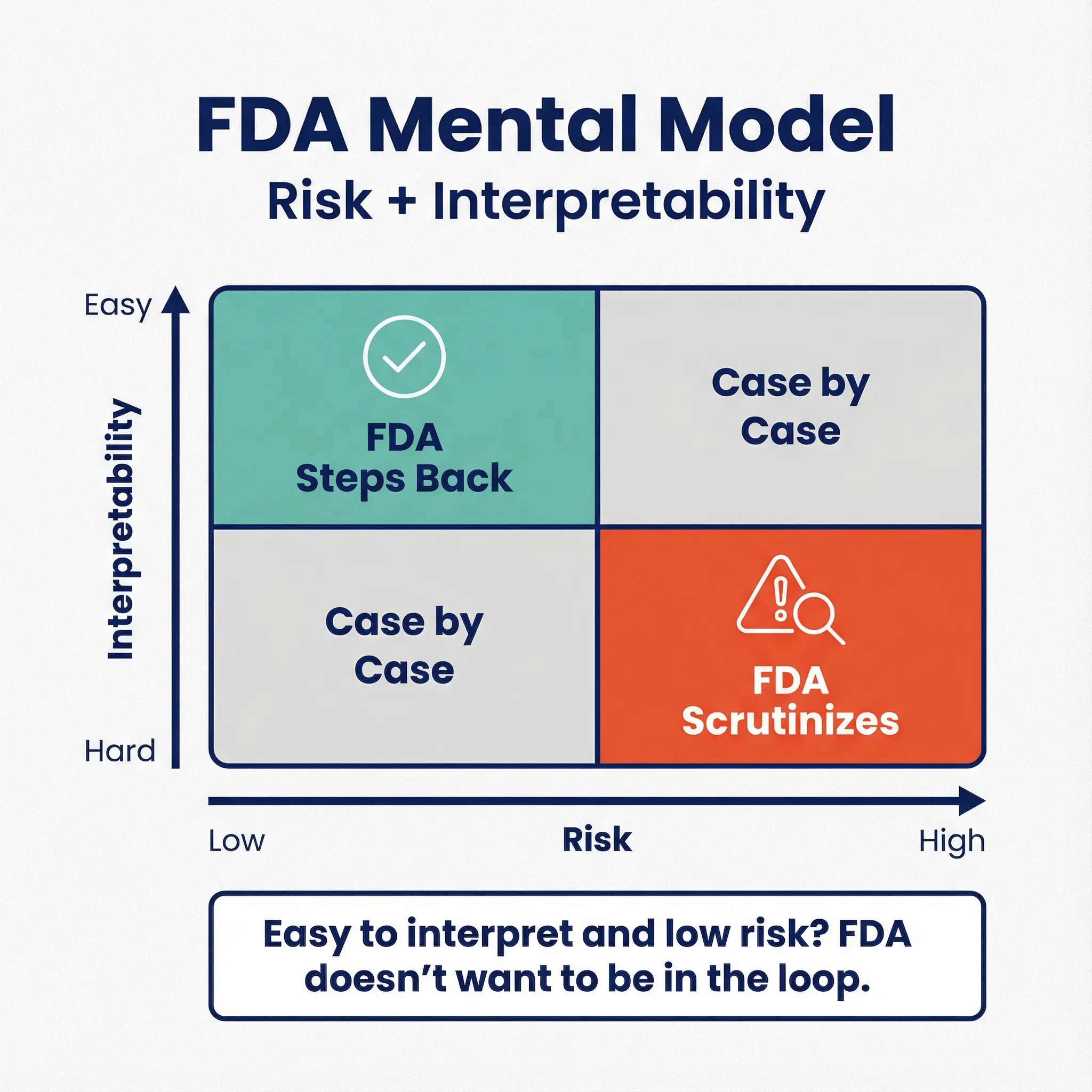

Here’s the mental model I think explains most of this. FDA is partly a “burden-of-proof refactoring” mechanism for healthcare. Instead of every hospital, clinician, payer, and patient running their own validation study to trust a product that can’t be explained in plain clinical language, FDA centralizes that evaluation for higher-risk tools. The common thread is risk plus interpretability:

- If it’s easy to interpret and low risk, FDA doesn’t want to be in the loop.

- If it’s hard to interpret, time-pressured, or creates strong automation bias, FDA wants either scrutiny or at least a clear boundary.

That’s also why “practice of medicine” matters. FDA generally doesn’t regulate how a clinician uses a legally marketed product on a specific patient; Congress carved out room for clinician judgment. But FDA does regulate what manufacturers market and distribute, especially when the product itself carries risk or creates misleading confidence.

General Wellness leans heavily on “as part of a healthy lifestyle” because lifestyle advice usually can’t hurt much when it’s framed at the right altitude.

This reminds me of a story from medical school that illustrates this point perfectly: we were caring for a plumber in the emergency department, and my attending physician made an observation that initially puzzled everyone. He turned to the plumber and said, "Your job is significantly harder than mine." Everyone in the room looked confused and surprised by this statement until he added the punchline: "Pipes don't fix themselves. People do."

When you recommend low-risk lifestyle habits—such as getting more sleep, eating more vegetables, or taking a daily walk—the body's inherent self-healing capacity and the relatively low stakes of being slightly wrong or imperfect in your recommendation form an important part of the safety case. This is why FDA can be comfortable stepping back from regulating products that offer this type of guidance: the biological system being advised has built-in resilience and correction mechanisms.

What was gray before, and is clearer now? 🔗

Clearer on the CDS side 🔗

These were murky in 2022, and the 2026 examples make the intended posture clearer:

-

Differential diagnosis tools that sometimes output a single clinically appropriate diagnosis Explicitly described as acceptable under the enforcement discretion framing when alternatives are highly improbable and the HCP reviews/finalizes.

In 2022, “specific output” was treated much more harshly.

- Guideline-based single pathway recommendations (care pathway selection) 2026 gives a chronic low back pain pathway example as potentially meeting the criteria, with an explicit warning that emergent/trauma acute back pain triage would not.

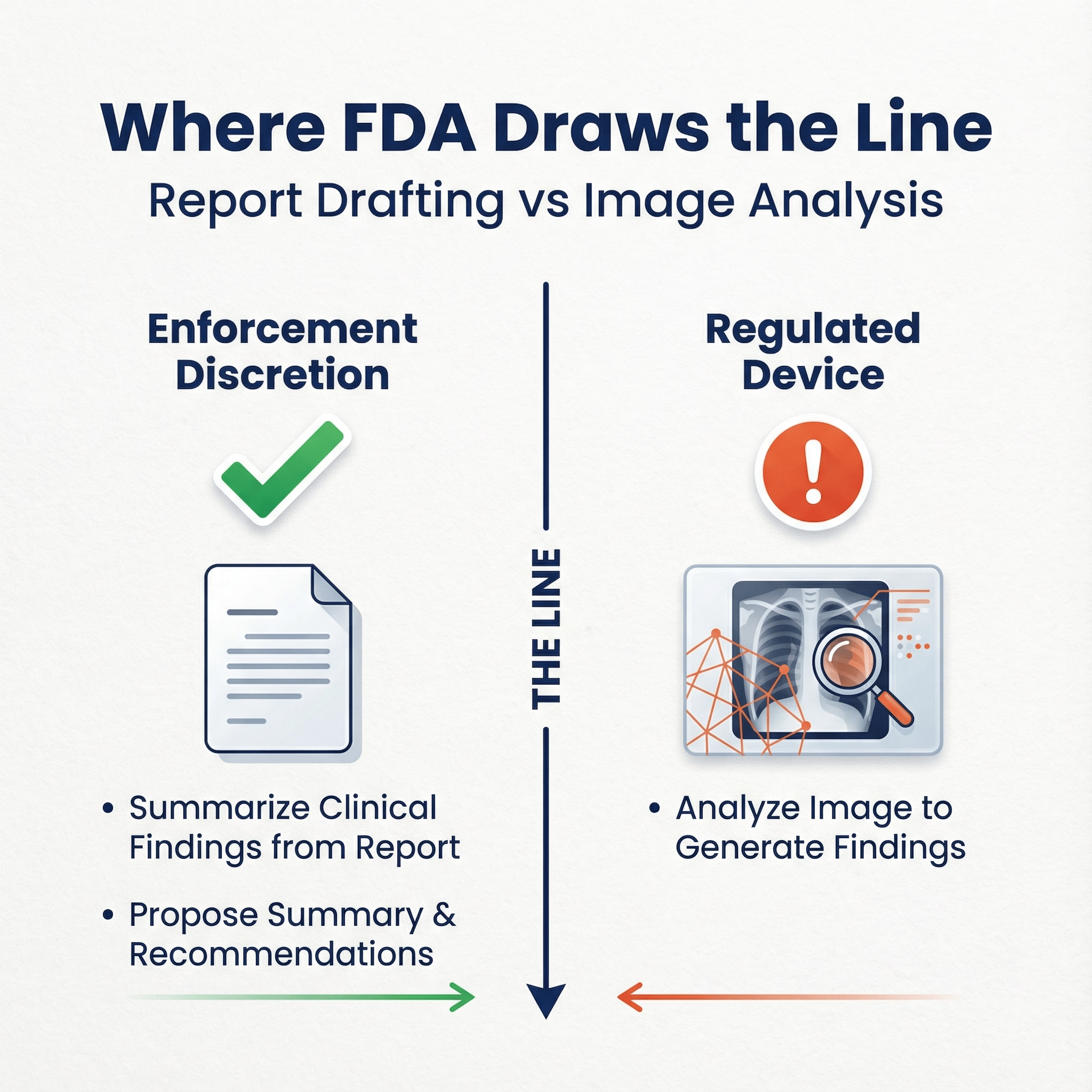

- Report drafting that uses radiologist findings but not the image 2026 draws a crisp line: summarize clinical findings from the report and propose summary and recommendation is one thing; analyzing the image to generate findings is a device.

- You can now recommend a treatment plan vs before it would fail criteria 3

Clearer on the Wellness side 🔗

- Non-invasive sensing outputs of physiologic parameters for “wellness” 2026 adds explicit criteria for when FDA “may consider” these as general wellness products, including validation guardrails if values mimic clinical ones.

- UI/marketing triggers that knock you out of wellness The “labeling, advertising, user interface, or functionality” list (disease references, diagnostic thresholds, alarms/prompts for clinical action, “medical grade” claims, substitution claims) is much more explicit than 2019.

Difficult cases that still deserve conservative handling 🔗

- LLM “triage” for mental health (even if clinician-facing) If it pushes urgency decisions (“send to ED now”) based on conversational signals, you’re in time-critical territory.

- Suicidality detection in patient chat High stakes, likely alarms, likely used for safety action. Expect device posture.

- Wearable biometrics with clinical-looking thresholds Even if the claim is “wellness,” UI that looks like clinical monitoring (zones, abnormal flags, alerts) invites FDA skepticism.

- LLM summarization that drifts into recommendations “Summarize” is often safe; “summarize and recommend next steps” changes the game.

- Multi-modal models (text + image + signals) The moment you process images or physiologic signals in a way that looks like diagnosis, you’re far from Non-Device CDS.

CDS vs General Wellness: Practical Contrast Using Examples 🔗

Example Set 1: Mental Health Chatbots 🔗

Mental health chatbots fall along a regulatory spectrum based on three factors: time-criticality, interpretability, and harm severity. On the left end sits the stress coach—think mindfulness prompts and lifestyle tips—which stays in general wellness territory because the stakes are low and clinicians can easily understand what it's doing. Move to the center and you hit virtual therapists that claim to treat conditions like depression or anxiety. These cross into device territory because treatment claims trigger FDA oversight, even if the underlying technology is similar. On the right end are suicide detection tools, which face the highest scrutiny due to time pressure (intervention windows are short), opacity (complex pattern recognition that's hard for clinicians to verify), and severity (life-or-death outcomes). The dividing line isn't the technology—it's how you position it. A chatbot using the same LLM can be unregulated wellness if framed as lifestyle coaching, or a Class II/III device if you claim it treats mental health conditions.

Example Set 2: Wearables and “Wellness Biometrics” 🔗

As I had correctly intuited when the WHOOP warning letter first broke, the reason WHOOP crossed the line is because the blood pressure measurement can be used to titrate medications, which could result in serious consequences like fainting. FDA also points to UI (gauge with colored target zones) and “medical-grade” marketing language, and says disclaimers didn’t overcome the intended use.

Again, this all makes sense when you understand the fundamental mental model of FDA. They are an evidence refactoring agency and a centralized risk management function. Physicians are not going to be able to ascertain if the Whoop blood pressure monitor is a one-to-one replacement of the standard of care. Therefore, making claims like "medical grade" crosses the line

The squishy scales: where FDA draws lines (and how to act on it) 🔗

FDA rarely gives numeric thresholds. Instead, they give examples. You can still extract useful “calibration points.” this is why I recommend reading the guidance documents, starting with the examples first. You can calibrate yourself first, and then read the text above it.

1) “Pattern” vs “discrete/episodic/intermittent” 🔗

2026 CDS defines “pattern” as multiple sequential or repeated measurements of a signal or signal acquisition system, and explicitly says point-in-time measurements generally don’t constitute a pattern by themselves.

From examples, a pragmatic interpretation looks like this:

- Likely “pattern”: continuous or frequent physiologic streams (ECG waveform/QRS; CGM; repeated RR intervals; frequent pulse ox).

- Likely “not pattern” (by itself): routine vitals at discrete encounters, discrete lab results, daily step counts.

Actionable conservative rule:

If your algorithm meaningfully depends on repeated measurements at sub-day cadence (especially minute-level to hourly), treat it as “pattern risk” unless you have a very strong argument otherwise. If your product is built on discrete results (labs, single vitals, encounter-based measurements) and you’re not reconstructing a continuous signal, you’re in a safer zone.

2) “Time-critical” isn’t only about ICU settings 🔗

CDS guidance repeatedly uses “time-critical decision-making” as the moment when recommendation-style software effectively becomes directive and higher risk.

Actionable conservative rule:

If the output is intended to trigger action within minutes to hours to prevent imminent harm (alarms, urgent escalation, dosing), assume FDA will treat it as device-like, even if you call it “support.”

3) “One clinically appropriate recommendation” is a narrow safe harbor 🔗

This is new and real, but it’s also narrow. FDA frames it as enforcement discretion only if the software otherwise meets CDS criteria.

Actionable conservative rule:

If you want to rely on the “one recommendation” posture, document why alternatives are “highly improbable” or clinically inappropriate in context, and make sure you’re not sneaking in a black-box risk model, unverified sources, or time-critical triggers.

FAQs 🔗

Q: I’m building a wellness chatbot using an LLM. What do I need to do?

Conservatively:

- Keep the intended use and UX squarely in general wellness categories (stress, sleep, fitness, nutrition) and “as part of a healthy lifestyle.”

- Make it so that your chatbot outputs recommend a healthy lifestyle as this cannot possibly harm anyone.

- Be very, very careful about what you say on your website. Marketing claims and how you present and label your product is everything

- Avoid diagnosing conditions, naming diseases in a way that implies management, giving medication guidance, or generating clinical thresholds/alerts.

- Add guardrails. Don’t rely on disclaimers alone.

Q: How does this affect my LLM-powered summarization tool?

If it’s physician-facing and summarizes records, guidelines, or reports without analyzing raw signals/images, it may align with Non-Device CDS or other digital health policies. If it starts recommending diagnosis/treatment without reviewability, you may drift into device territory.

General Wellness: use, oversight, and marketing 🔗

Q: Can a patient use a general wellness app without physician oversight? Can the developer claim this is OK?

Yes. General wellness is framed around self-directed healthy lifestyle or general health uses, and it’s commonly consumer-facing. The developer can claim it’s for general wellness if the intended use and labeling stay within those boundaries and the product is low risk.

Q: Can a physician use a general wellness app during a patient encounter? Can the developer claim this is OK?

A physician can use almost anything in practice, but that doesn’t define the product’s intended use. The developer can say clinicians may use it for general wellness counseling, but avoid marketing that turns it into disease management (thresholds, treatment prompts, “clinical grade,” etc.).

Q: Are all general wellness products used by patients, or can physicians use them for patients?

Both can use them. “General wellness” is about intended use and risk, not the job title of the person holding the phone. The developer should be careful that “for physicians” language doesn’t drift into diagnosis/monitoring/management claims.

Q: Can a general wellness app say it is “for physicians” to use?

It can, but it’s risky marketing. If the app is truly wellness-only, keep the claims and UI anchored in wellness. Once you’re selling it as a clinical tool, FDA will look for clinical intended use signals.

CDS vs patient use 🔗

Q: Can a patient use a CDS app on their own? Can the developer claim this is OK?

A patient can use anything. The question is what the developer can claim. If the app provides patient-facing preventive/diagnostic/treatment recommendations, FDA says that kind of function meets the definition of a device (Non-Device CDS is HCP-focused).

So a developer generally cannot claim “Non-Device CDS” for a patient-facing CDS tool.

ChatGPT Health and LLM-based apps 🔗

Q: Is “ChatGPT for health questions” a medical device?

It depends on intended use and how it’s packaged/marketed. A general-purpose chatbot that provides general information is different from a product marketed to diagnose, treat, or manage disease. The CDS guidance emphasizes intended users and recommendations, and the wellness guidance emphasizes lifestyle scope and avoidance of clinical triggers.

Q: I’m building an LLM tool “just for physicians.” Do I need to collect a medical license number?

Not as a formal FDA requirement for classification. But gating can be a useful risk-control and evidence of intended user. It won’t save you if the functionality and claims are device-like, but it can reduce patient misuse and help align with your intended-use story.

Q: I’m building an LLM tool “just for patients.” Do I need to verify it’s not a physician using it?

No, that’s usually unnecessary. A physician using a patient-facing tool doesn’t increase regulatory risk; the product’s intended use and labeling do. Focus on whether patient-facing outputs cross into diagnosis/treatment/management.

Q: If my chatbot is asked questions outside general wellness or outside Non-Device CDS, should I install safeguards?

Yes, if you want a credible “we designed for the intended use” posture. The 2026 wellness guidance explicitly treats UI/functionality as part of intended use. If your bot routinely produces disease-specific management guidance, a disclaimer won’t carry much weight.

Practical safeguards:

- Topic classifiers (wellness vs medical management vs emergency).

- Hard refusals for medication dosing, diagnosis, emergent triage.

- Escalation prompts (“seek professional evaluation”) that do not name a disease or declare abnormality.

- Retrieval-only mode for clinician tools with citations.

- Logging + monitoring for drift.

Q: As an app developer, do I need to constrain outputs, or can I just tell users not to use it in a way that makes it a device?

Conservatively, constrain outputs. FDA repeatedly treats labeling, advertising, UI, and functionality as evidence of intended use. If the product can easily be used to produce disease management outputs and you know it, disclaimers alone are a weak control.

Mental health specifics 🔗

Q: Is a “virtual therapist” chatbot general wellness?

If it claims to treat depression/anxiety disorders or provides therapy as treatment, it’s outside general wellness. General wellness covers stress management and lifestyle support, not disease treatment.

Q: Suicide detector vs virtual therapist: which is more likely a device?

Both can be devices, but the suicide detector has higher immediate risk because it’s closer to time-critical safety action. The CDS guidance’s time-critical lens is the closest analog: when immediate action is required, risk rises and “support” starts to look like directive automation.

Q: What about mental health risk scoring used by psychologists?

If it’s used to support clinical decisions and is clinician-facing, you evaluate it under CDS logic:

- Is it based on discrete medical information vs signals/patterns?

- Is it time-critical (imminent harm) vs longer-term planning?

- Can the psychologist independently review the basis?

A conservative posture:

- Near-term suicide risk scoring or “urgent triage now” outputs should be treated as device-like.

- Longer-horizon planning scores (months) with transparent, evidence-based basis may be closer to the enforcement discretion examples (planning/shared decision-making), depending on implementation.

LLM summarization, images, ECG, CGM, risk prediction 🔗

Q: How does this affect my LLM-powered summarization tool?

If it’s physician-facing and summarizes records, guidelines, or reports without analyzing raw signals/images, it may align with Non-Device CDS or other digital health policies. If it starts recommending diagnosis/treatment without reviewability, you may drift into device territory.

Q: What if my summarization tool analyzes images?

If it processes medical images to generate clinical findings, that fails CDS Criterion 1 and is device-like.

Q: What if my vision-language model summarizes images (LVM looks at images)?

Same answer. Image analysis that produces clinical interpretation is not Non-Device CDS under Criterion 1.

Q: What if my LLM processes ECG signals?

ECG waveform/QRS are explicitly treated as patterns, which fails Criterion 1 for Non-Device CDS. That’s device-like.

Q: What if my LLM takes at-home blood pressure readings and returns a 5-year stroke risk?

- Patient-facing: likely device (disease risk prediction to patient).

- Clinician-facing: you’re in CDS territory, but risk prediction outputs can still be seen as “specific outputs.” 2026 softened this area with enforcement discretion examples (risk estimates for planning), but you should assume device unless you tightly align with the examples: evidence-based, transparent, not time-critical, and reviewable.

Q: What if my LLM takes CGM readings and returns a 20-minute hypoglycemia risk?

That’s time-critical and based on a pattern stream. The CDS guidance treats CGM pattern analysis and time-critical decision support as device-like.

Where This Leaves You 🔗

The 2026 updates aren't the seismic shift some headlines suggest. FDA clarified definitions, tightened a few examples, and added narrow enforcement discretion for edge cases. Most of the underlying philosophy remains intact: FDA steps back when risk is low and interpretability is high, and leans in when products create meaningful patient harm or automation bias.

For teams building in this space, the practical takeaway is this: know where your product sits on the risk and interpretability matrix, and be honest about it. If you're truly in general wellness territory with low-risk lifestyle guidance, the path is clearer now than before. If you're processing physiologic patterns, making time-critical recommendations, or analyzing medical images, expect device-level scrutiny regardless of how you frame the output.

The gray zones haven't disappeared. LLM-based tools, mental health applications, and wearables with clinical-adjacent features still require careful positioning. The difference is that FDA has given you better calibration points to work from.

If you're uncertain about where your product lands, don't guess. The cost of getting this wrong—whether it's an unexpected warning letter, a delayed launch, or a full regulatory submission when you thought you were exempt—far exceeds the cost of getting expert input up front. Better safe than sorry.

We help companies navigate exactly these questions every day. If you're building an AI/ML tool in healthcare and want to pressure-test your regulatory strategy. We'll help you figure out the right path forward.