Innolitics introduction 🔗

Innolitics provides US FDA regulatory consulting to startups and established medical-device companies. We’re experts with medical-device software, cybersecurity, and AI/ML. See our services and solutions pages for more details.

We have practicing software engineers on our team, so unlike many regulatory firms, we speak both “software” and “regulatory”. We can guide your team through the process of writing software validation and cybersecurity documentation and we can even accelerate the process and write much of the documentation for you (see our Fast 510(k) Solution).

About this Transcript 🔗

This document is a transcript of an official FDA (or IMDRF) guidance document. We transcribe the official PDFs into HTML so that we can share links to particular sections of the guidance when communicating internally and with our clients. We do our best to be accurate and have a thorough review process, but occasionally mistakes slip through. If you notice a typo, please email a screenshot of it to Mihajlo at mgrcic@innolitics.com so we can fix it.

Preamble 🔗

Document issued on October 26th, 2016.

Draft document issued on .

For questions about this document, contact the FDA Office of Minority Health at 240-402-5084 or omh@fda.hhs.gov.

Contains non-binding guidance.

I. INTRODUCTION 🔗

The purpose of this guidance is to provide FDA expectations for and recommendations on the use of a standardized approach for collecting and reporting race and ethnicity data in submissions for clinical trials for FDA-regulated medical products conducted in the United States and abroad. Using standard terminology for age, sex, gender, race, and ethnicity helps ensure that subpopulation data is collected consistently. The recommended standardized approach is based on the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Directive 151 and developed in accordance with section 4302 of the Affordable Care Act2, the HHS Implementation Guidance on Data Collection Standards for Race, Ethnicity, Sex, Primary Language, and Disability Status3, and the Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act4 (FDASIA) Section 907 Action Plan5. This guidance lists the OMB categories for race and ethnicity and describes FDA's reasons for recommending the use of these categories in medical product (drugs, biologics, and devices) applications. In addition, this guidance recommends a format for collection of race and ethnicity clinical trial data that are submitted in standardized data sets per the Study Data Tabulation Model6, in the electronic Common Technical Document (eCTD)7, and as specified in FDA’s Guidance on providing regulatory submissions in electronic format8.

This document is intended to provide guidance on:

- Meeting the requirements set forth in the 1998 final rule9 regarding the presentation of demographic data on investigational new drug (IND) applications and new drug applications (NDAs) (known as the “Demographic Rule”) and the collection of race and ethnicity data in biologics license applications (BLAs) and medical device applications

- Addressing the FDA Safety and Innovation Act, Section 907 Action Plan⁶ to improve demographic subgroup gaps in data quality

FDA's guidance documents, including this guidance, do not establish legally enforceable responsibilities. Instead, guidances describe the Agency's current thinking on a topic and should be viewed only as recommendations, unless specific regulatory or statutory requirements are cited. The use of the word should in Agency guidances means that something is suggested or recommended, but not required.

II. SCOPE 🔗

This document is intended to provide guidance on the collection of race and ethnicity in clinical trials. This guidance provides clarifying recommendations on the two-step collection process of race and ethnicity data and has been developed in support of the FDASIA 907 Action Plan to improve the completeness and quality of demographic subgroup data. This guidance replaces the 2005 FDA guidance on Collection of Race and Ethnicity in Clinical Trials.10

For drugs, the Demographic Rule requires IND holders to tabulate in their annual report the number of participants enrolled in clinical trials by age, race, and gender11 and requires sponsors of NDAs to include summaries of effectiveness and safety data for important demographic subgroups, including racial subgroups.12 FDA also strongly recommends the collection and reporting of ethnicity data (Hispanic-Latino/not Hispanic-Latino) consistent with OMB standards and guidelines.²

This guidance is also intended to help applicants in preparing BLAs.

For medical devices, FDA also recommends application sponsors collect ethnicity and race data in accordance with the OMB recommendations², the information collection standards discussed in this guidance document, and, when finalized, the Center for Devices and Radiologic Health (CDRH) and Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) Age/Race/Ethnicity draft guidance document.13

FDA expectations are that sponsors enroll participants who reflect the demographics for clinically relevant populations with regard to age, gender, race, and ethnicity.¹³ A plan to address inclusion of clinically relevant subpopulations should be submitted for discussion to the Agency at the earliest phase of development and, for drugs and biologics, no later than the end of the phase 2 meeting. Inadequate participation and/or data analyses from clinically relevant subpopulations can lead to insufficient information pertaining to medical product safety and effectiveness for product labeling. Patient characteristics such as age, sex, gender, geographic location (e.g. rural), emotional, physical, sensory, and cognitive capabilities can often be important variables when evaluating medical product safety and efficacy. However, these will not be addressed within this guidance.

This guidance does not address the level of participation of racial and ethnic groups in clinical trials. For questions related to the level of participation or the size of a trial, sponsors should consult with the review division of the appropriate centers and office14’15’16 for guidance on clinical trial design and demographic sub-groups prior to the start of a trial.

III. BACKGROUND 🔗

Over recent decades, the Agency’s views, as well as those of the medical community, have evolved regarding the collection of race and ethnicity information in clinical studies.

Prior to developing the recommendations set forth in this guidance, FDA publicly sought input from a variety of experts and stakeholders regarding the study and evaluation of age, race, and ethnicity in clinical studies for medical products. On April 1, 2014, FDA convened a public hearing17’18 for feedback on the findings of the FDASIA 907 Report to obtain input on the issues and challenges associated with the collection, analysis, and availability of demographic subgroup data (i.e., age, sex, race, and ethnicity) in applications for approval of FDA-regulated medical products.¹⁸’19 FDA also opened a public docket for further input. On April 9, 2015²⁰ and December 2, 2015,20 various government agencies, physician professional societies, and patient advocacy groups participated in public workshops to discuss strategies for ensuring diversity, inclusion, and meaningful participation in clinical trials. This guidance reflects the concerns and recommendations generated in these and other public fora. The following is a brief history of the adoption of the OMB categories for reporting of race and ethnicity data by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and FDA.

A. Department of Health and Human Services Report and Guidance 🔗

In 1999, HHS issued a report, Improving the Collection and Use of Racial and Ethnic Data in HHS.**21 The report describes HHS policy on collecting and reporting data on race and ethnicity for HHS programs. The report asks for the inclusion of race and ethnicity categories in HHS-funded and sponsored data collection and reporting systems in all HHS programs, including in both health and human services. The policy was developed to (1) help monitor HHS programs, (2) determine whether Federal funds are being used in a nondiscriminatory manner, and (3) promote the availability of standard race and ethnicity data across various agencies to facilitate HHS responses to major health and human services issues. This policy, updated in 2011,⁴ clearly states that the minimum standard categories in OMB Policy Directive 15² should be used when collecting and reporting data in HHS data systems or reporting HHS-funded statistics.22

B. ICH E5 - Guidance on Ethnic Factors in the Acceptability of Foreign Clinical Data 🔗

In 1999, as part of an international effort by the United States and others to harmonize technical requirements for pharmaceutical drug development and regulation (the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH)), the FDA published a guidance entitled E5 Guidance on Ethnic Factors in the Acceptability of Foreign Clinical Data**23 (63 FR 31790, June 10, 1998), that described how clinical data collected in one region could be used in the registration or approval of a drug or biological product in another region, taking into account the influence of ethnic factors. The E5 guidance defines ethnic factors that affect response in terms of both intrinsic and extrinsic issues. Because differences in ethnic factors have the potential to affect responses in some subpopulations, the E5 guidance provides a general framework for evaluating medicines with regard to their sensitivity to ethnic factors. In particular, the Question and Answer Addendum to E5 introduces the multi-regional clinical trial study design as one means to evaluate treatment response heterogeneity and extrapolation. Multi-regional clinical trials may present special situations for the collection and self-reporting of race and ethnicity.

C. National Institutes of Health Initiatives, Revitalization Act 🔗

In 1993, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Revitalization Act24 directed NIH to establish guidelines for including women and minorities in NIH-sponsored clinical research.25 In 2001, NIH was directed26 to ensure that women and minorities were included as participants unless their exclusion was justified due to circumstances specified by NIH guidelines. Furthermore, clinical trials were to be designed and carried out in a manner that would elicit information across genders and diverse racial and ethnic subgroups to examine differential effects on such groups.

NIH guidelines stipulate that when proposing a phase 3 clinical trial, evidence must be reviewed to establish whether or not there are potentially clinically important sex- and racial/ethnic-based differences in the anticipated effects of the intervention. If previous studies support the existence of significant differences, the primary questions and design of the trial must specifically accommodate this. For example, if men and women are thought to respond differently to an intervention, then the phase 3 clinical trial must be designed to answer two separate primary questions, one for men and the other for women. When prior studies support no significant differences for either sex/gender or racial/ethnic subgroups with a given intervention, then sex/gender and racial/ethnic status will not be required as subject selection criteria, although the inclusion and analysis by gender and racial/ethnic groups is strongly encouraged. When prior studies neither support nor negate significant differences, then the design of the phase 3 clinical trial will be required to include sufficient and appropriate entry of sex/gender and racial/ethnic participants so that valid analysis of the intervention effects can be performed. However, the trial will not be required to provide high statistical power for these comparisons.

D. FDA Regulations, Guidances, and Section 907 of the Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act of 2012 (FDASIA) 🔗

In 1997, OMB issued its revised recommendations for the collection and use of race and ethnicity data by Federal agencies (Policy Directive 15).² OMB stated that its race and ethnicity categories were not anthropologically or scientifically-based designations but instead were categories that described the sociocultural construct of our society.

As outlined in FDA’s 2005 Guidance on Collection of Race and Ethnicity in Clinical Trials,¹¹ FDA recommended the use of the standardized OMB race and ethnicity categories for data collection in clinical trials for two reasons. First, the use of the recommended OMB categories will help ensure consistency in demographic subset analyses in applications submitted to FDA¹³ and in data collected by other government agencies. Second, consistency in these categories may make the demographic subset analysis more useful in evaluating potential differences in the safety and effectiveness of medical products among population subgroups. To assess potential subgroup differences in a meaningful way, it is important to use uniform, standard methods of defining racial and ethnic subgroups.

FDA regulations require sponsors of Investigational New Drugs (INDs)27 to report the total number of subjects initially planned for inclusion in the study; the number entered into the study to date, tabulated by age group, gender, and race; the number whose participation in the study was completed as planned; and the number who dropped out of the study for any reason. FDA regulations for NDAs require sponsors to present a summary of safety and effectiveness data by demographic subgroups (age, sex, race, and other subgroups as appropriate),28 as well as an analysis of whether modifications of dose or dosage intervals are needed for specific subgroups.29 FDA recommends the identification of a subject’s race and/or ethnicity in such summaries.

Section 907 of FDASIA directed the Agency to develop a report30 “addressing the extent to which clinical trial participation and the inclusion of safety and effectiveness data by demographic subgroups, including sex, age, race, and ethnicity, is included in applications submitted to the Food and Drug Administration.” Section 907 also directed FDA to develop an action plan outlining “recommendations for improving the completeness and quality of analyses of data on demographic subgroups in summaries of product safety and effectiveness data and in labeling; on the inclusion of such data, or the lack of availability of such data, in labeling; and on improving the public availability of such data to patients, health care providers, and researchers.” In support of that Action Plan, FDA has developed this guidance as one of the actions to improve the completeness and quality of demographic subgroup data.

Relevance of Population Subgroup Studies 🔗

Differences in response to medical products have already been observed in racially and ethnically distinct subgroups of the U.S. population.31 These differences may be attributable to intrinsic factors (e.g., genetics, metabolism, elimination), extrinsic factors (e.g., diet, environmental exposure, sociocultural issues), or interactions between these factors (Huang 2008).32

An FDA review of drug approvals between 2008 and 2013 found that approximately one-fifth of new drugs demonstrated some differences in exposure and/or response across racial/ethnic groups (Ramamoorthy 2015).33 For example, racial differences in skin structure and physiology can affect response to dermatologic and topically applied products (Taylor 2002).34 Mortality rates of patients on dialysis have been shown to differ across race and ethnicity groups.35 Several studies have also shown that Blacks respond less well to several classes of antihypertensive agents (beta blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors) (Exner 2001 and Yancy 2001).36’37 For cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6), an important enzyme that metabolizes drugs belonging to a variety of therapeutic areas such as antidepressants, antipsychotics, and beta blockers, the frequency of poor metabolizers is higher in Whites38 (7-10%) and Blacks or African Americans (3-8%) than in persons of Asian heritage (Xie 2001).39 The incidence of anticonvulsant carbamazepine40-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome-toxic epidermal necrolysis has shown a strong association with HLA-B*1502 (Chung 200441), an allele that is highly prevalent in Asian populations (particularly Chinese) when compared to non-Asian populations (Hung 200642 and Alfirevic 200643).

Collecting data on race and/or ethnicity is critical to identifying population-specific signals. As illustrated above, genetic studies may explain the basis for observed differences in pharmacokinetics, efficacy, or safety across racial or ethnic subgroups, and FDA has recommended collection of DNA samples in clinical trials for such purposes.44 FDA has also published guidance on enrichment strategies for selecting participants for clinical trials based on prognostic or predictive biomarkers (such as genotype).45

IV. COLLECTING RACE AND ETHNICITY DATA IN CLINICAL TRIALS 🔗

The classifications discussed below provide a minimum standard for maintaining, collecting, and presenting data on race and ethnicity for Federal reporting purposes. Consistent with OMB Policy Directive 15, the categories in this classification are social-political constructs and should not be interpreted as being scientific or anthropological in nature. They are not to be used as determinants of eligibility for participation in any Federal program. The standards have been developed to provide a common framework for uniformity and consistency in the collection and use of data on race and ethnicity by Federal agencies.

The recommendations in this section reflect the Agency's commitment to and expectations for more consistent demographic subgroup data collection. For studies conducted both inside and outside the United States, the Agency recommends the following process, which is based on the current OMB Directive for collecting racial and ethnic data. These recommendations are also consistent with the format for collecting race and ethnicity data set forth in NIH guidance.46

A. Two-Question Format 🔗

In order to be consistent with OMB and other recommended best practices, FDA recommends using the two-question format for requesting race and ethnicity information, with the ethnicity question preceding the question about race. Example:

Question 1 (answer first): Do you consider yourself Hispanic/Latino or not Hispanic/Latino?

Question 2 (answer second): Which of the following five racial designations best describes you? More than one choice is acceptable.

B. Self-Reporting 🔗

FDA recommends that trial participants self-report race and ethnicity information and that individuals be permitted to designate a multiracial identity. When the collection of self-reported designations is not feasible (e.g., because of the subject’s inability to respond), it is recommended that the information be requested from a first-degree relative or other knowledgeable source. Race and ethnicity should not be assigned by the study team conducting the trial.

C. Ethnicity 🔗

For ethnicity, we recommend the following minimum choices be offered:

Hispanic or Latino: A person of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin, regardless of race. The term "Spanish origin" can be used in addition to "Hispanic or Latino."

Not Hispanic or Latino

D. Race 🔗

For race, we recommend the following minimum choices be offered:

- American Indian or Alaska Native: A person having origins in any of the original peoples of North and South America (including Central America), and who maintains tribal affiliation or community attachment.

- Asian: A person having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent, including, for example, Cambodia, China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippine Islands, Thailand, and Vietnam.

- Black or African American: A person having origins in any of the black racial groups of Africa. Terms such as "Haitian" or "Negro" can be used in addition to "Black or African American."

- Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander: A person having origins in any of the original peoples of Hawaii, Guam, Samoa, or other Pacific Islands.

- White: A person having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa.

We recommend offering an option of selecting one or more racial designations or additional subgroup designations. Recommended forms for the instruction accompanying the multiple-response questions are “Mark one or more” and “Select one or more.”

Sponsors should report the number of respondents in each racial category who self-reported as Hispanic or Latino. When aggregate data are presented, data producers should provide the number of respondents who marked (or selected) only one category, separately for each of the five racial categories. In addition to these numbers, data producers are encouraged to provide the detailed distributions, including all possible combinations of multiple responses to the race question.

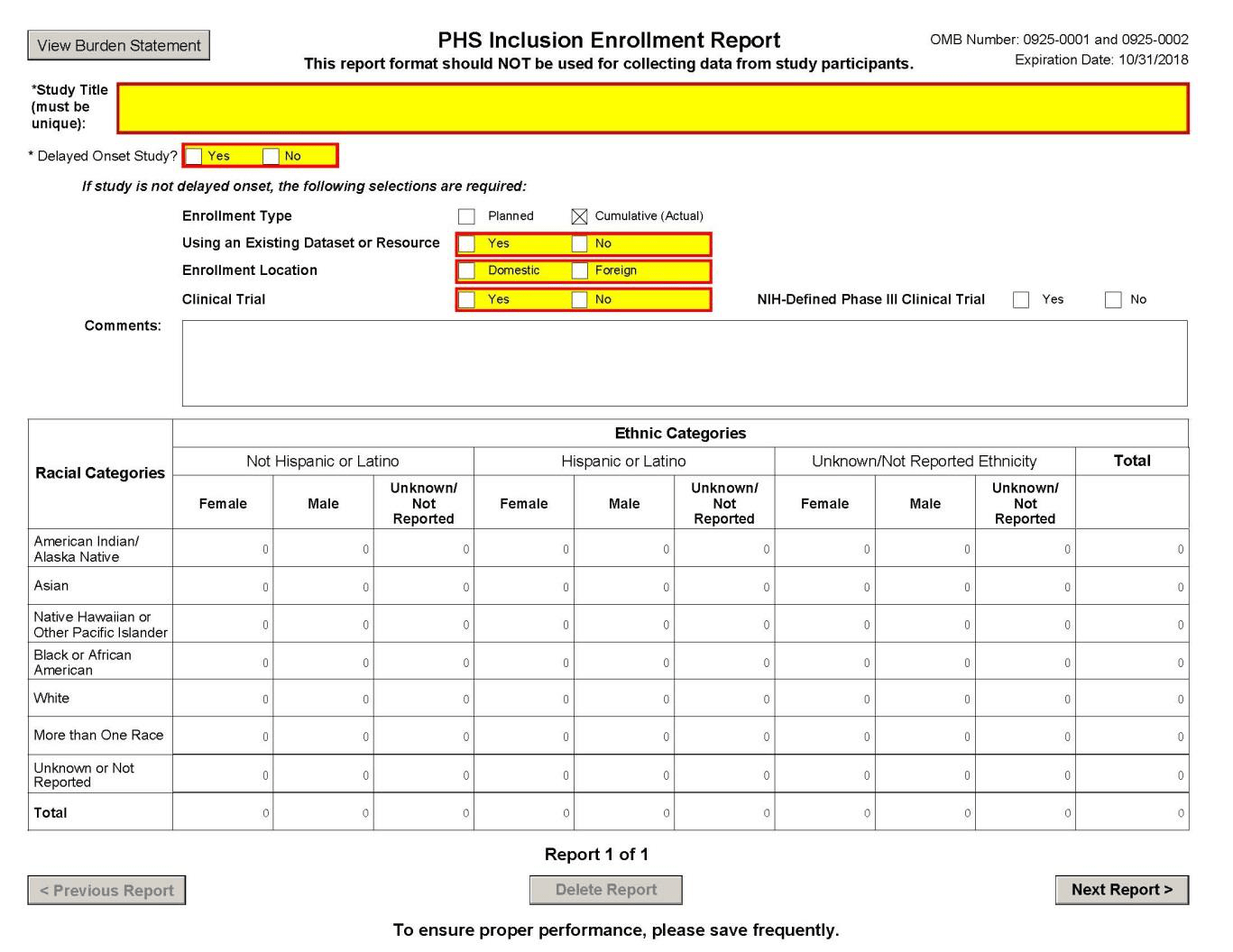

If data on multiple responses are collapsed, at a minimum, the total number of respondents reporting “more than one race” shall be made available (see attached NIH PHS Inclusion Enrollment Report form47).

E. Use of More Detailed Racial and Ethnic Categories 🔗

In certain situations, as recommended in OMB Policy Directive 15, more detailed race and ethnicity information may be desired. For example, for clinical trials conducted outside the United States, FDA recognizes that the recommended categories for race and ethnicity were developed in the United States and that these categories may not adequately describe racial and ethnic groups in foreign countries. Furthermore, White can reflect origins in Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa; Asian can reflect origins from areas ranging from India to Japan.

In situations where appropriate, FDA recommends using more detailed categories by geographic region to provide sponsors the flexibility to adequately characterize race and ethnicity. As outlined in the 2011 HHS Implementation Guidance on Data Collection Standards for Race, Ethnicity, Sex, Primary Language, and Disability Status,⁴ if additional granularity or more detailed characterizations of race or ethnicity are collected to enhance understanding of the trial participants, FDA recommends these characterizations be traceable to the five minimum designations for race and the two designations for ethnicity listed in sections D and C above. Example (from the above-referenced 2011 HHS Guidance⁴):

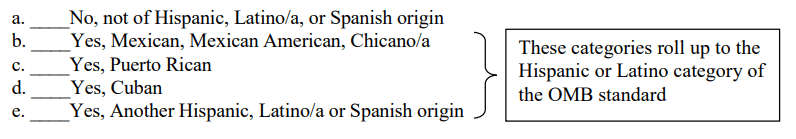

Ethnicity Data Standard

Are you Hispanic, Latino/a, or of Spanish origin? (One or more categories may be selected)

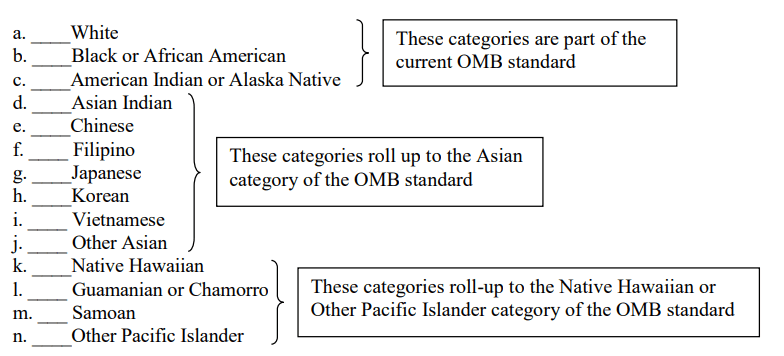

Race Data Standard

What is your race? (One or more categories may be selected)

Where concerns exist in the representation of race or ethnicity categories, sponsors are encouraged to discuss the race or ethnicity issues with the appropriate review division.

F. Use of the term “nonwhite” 🔗

The term “nonwhite” is not acceptable for use in the presentation of Federal Government data. It should not be used in publication or text of any report.

V. PRESENTATION OF CLINICAL TRIAL RACE AND ETHNICITY DATA 🔗

For INDs, NDAs, and BLAs, we recommend the submission of tabulated demographic data¹⁰’¹³ based on the Demographic Rule for all clinical trials using the characterizations of race and ethnicity described in this guidance. Beginning in May 2017, CDER and CBER will require marketing applications to be submitted electronically.48 CDER and CBER use the eCTD as the standard for their electronic applications. When submitting an electronic application, the presentation of demographic data is described in ICH M4E eCTD Guidance (section 2.7.4.1.3 and table 2.7.4.2),49 which suggests a tabular display of demographic characteristics (e.g., age, sex, race) by treatment group (e.g., active drug, placebo).50 With regard to the description of race and ethnicity, the categories suggested previously in this document (Section IV) provide more detail than those suggested in the ICH M4E eCTD Guidance. FDA recommends that sponsors provide the level of detail described in Section IV of this guidance. For relevant device submissions, we recommend following the guidance presented here and, when finalized, the recommendations in the draft guidance documents Evaluation and Reporting of Age, Race, and Ethnicity Data in Medical Device Clinical Studies.¹⁴

VI. REFERENCES 🔗

- Alfirevic A, Jorgensen AL, Williamson PR, Chadwick DW, Park BK, Pirmohamed M. 2006. “HLA-B locus in Caucasian patients with carbamazepine hypersensitivity.” Pharmacogenomics, 7:813-818.

- Chung WH, Hung SI, Hong HS, Hsih MS, Yang LC, et al. 2004. “A Marker for Stevens-Johnson Syndrome.” Nature, 428:486.

- Exner D, Dries D, Donamski M, and Cohn J. 2001. “Lesser Response to Angiotensin-Converting-Enzyme Inhibitor Therapy in Black as Compared with White Patients With Left Ventricular Dysfunction.” N Engl J Med, 344:1351-1357.

- Huang SM, Temple R. 2008. “Is this the drug or dose for you? Impact and consideration of ethnic factors in global drug development, regulatory review, and clinical practice.” Clin Pharmacol Ther, 84:287-294.

- Hung SI, Chung WH, Jee SH, Chen WC, Chang YT, et al. 2006. “Genetic Susceptibility to Carbamazepine-Induced Cutaneous Adverse Drug Reactions.” Pharmacogenetics and Genomics, 16:297-306.

- Ramamoorthy A, Pacanowski MA, Bull J, and Zhang L. 2015. "Racial/ethnic differences in drug disposition and response: review of recently approved drugs." Clin Pharmacol Ther, 97:263-273.

- Taylor S. 2002. “Skin of Color: Biology, Structure, Function, and Implications for Dermatologic Disease.” Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 46:S41-62.

- Xie H, Kim R, Wood A, and Stein C. 2001. “Molecular Basis of Ethnic Differences in Drug Disposition and Response.” Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol, 41:815-850.

- Yan, Guofen, et al. 2013. "The relationship of age, race, and ethnicity with survival in dialysis patients." Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 8(6):953-961.

- Yancy C, Fowler M, Colucci W, Gilbert E, Bristow M, et al. 2001. “Race and the Response to Adrenergic Blockade with Carvedilol in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure.” N Engl J Med, 344:1358-1365.

VII. BIBLIOGRAPHY 🔗

HHS Policy and Reports 🔗

- Policy Statement on Inclusion of Race and Ethnicity in DHHS Data Collection Activities (October 24, 1997)

- Improving the Collection and Use of Racial and Ethnic Data in HHS (December 1, 1999)

- US Department of HHS Implementation Guidance on Data Collection Standards for Race, Ethnicity, Sex, Primary Language, and Disability Status (October 31, 2011)

NIH Policies, Reports, and Resources 🔗

- NIH Revitalization Act of 1993, Subtitle B (PL 103-43) (June 10, 1993)

- NIH Policy on Reporting Race and Ethnicity Data: Subjects in Clinical Research (August 8, 2001)

- NIH Guidelines on the Inclusion of Women and Minorities as Subjects in Clinical Research (October 2001)

- Use of New Inclusion Management System Required as of October 17, 2014 (October 2, 2014)

- NIH PHS Inclusion Enrollment Report Form (March 25, 2015)

- NIH Policy Implementation Page: Inclusion of Women and Minorities as Participants in Research Involving Human Subjects

FDA Regulations, Reports, and Legislation 🔗

- Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997 (Public Law 105-115) (November 21, 1997)

- Investigational New Drug Applications and New Drug Applications (21 CFR 312 and 314) (February 11, 1998)

- Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act (FDAAA) of 2007 (Public Law No. 110-85 Section 901 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act) (September 2009)

- FDA Safety and Innovation Act (Public Law No. 112-114) (February 9, 2012)

- FDA Report: Collection, Analysis, and Availability of Demographic Subgroup Data for FDA-Approved Medical Products (August 2013)

- FDA Action Plan to Enhance the Collection and Availability of Demographic Subgroup Data (August 2014)

- Investigational New Drug Applications and New Drug Applications (21 CFR 314.50(b)) (April 1, 2015)

FDA Guidances for Industry 🔗

- Guideline for the Study and Evaluation of Gender Differences in the Clinical Evaluation of Drugs (July 1993)

- General Considerations for the Clinical Evaluation of Drugs (February 1997)

- Guidance on IDE Policies and Procedures (January 1998)

- Format and Content of the Clinical and Statistical Sections of an Application (July 1998)

- M4E: The CTD -- Efficacy (August 2001)

- Content and Format for Geriatric Labeling (October 2001)

- Pharmacokinetics in Patients with Impaired Hepatic Function: Study Design, Data Analysis, and Impact on Dosing and Labeling (May 2003)

- Collection of Race and Ethnicity Data in Clinical Trials (September 2005)

- Clinical Studies Section of Labeling for Human Prescription Drugs and Biological Products -- Content and Format (January 2006)

- Adverse Reactions Section of Labeling for Human Prescription Drugs and Biological Products -- Content and Format (January 2006)

- Clinical Pharmacogenomics: Premarket Evaluation in Early-Phase Clinical Studies and Recommendations for Labeling (January 2013)

- Design Considerations for Pivotal Clinical Investigations for Medical Devices (November 2013)

- Evaluation of Sex-Specific Data in Medical Device Clinical Studies (August 2014)

- General Clinical Pharmacology Considerations for Pediatric Studies for Drugs and Biological Products (December 2014)

- Providing Regulatory Submissions in Electronic Format -- Standardized Study Data (December 2014)

- Providing Regulatory Submissions in Electronic Format -- Certain Human Pharmaceutical Product Applications and Related Submissions Using the eCTD Specifications (May 2015)

- Integrated Summary of Effectiveness Guidance for Industry (October 2015)

- Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1 Infection: Developing Antiretroviral Drugs for Treatment (November 2015)

- Study Data Technical Conformance Guide (March 2016)

- Draft Guidance: Diabetes Mellitus -- Developing Drugs and Therapeutic Biologics for Treatment and Prevention (February 2008)

- Draft Guidance: Pharmacokinetics in Patients with Impaired Renal Function -- Study Design, Data Analysis, and Impact on Dosing and Labeling (March 2010)

- Draft Guidance: Drug Interaction Studies -- Study Design, Data Analysis, Implications for Dosing and Labeling Recommendations (February 2012)

- Draft Guidance: Enrichment Strategies for Clinical Trials to Support Approval of Human Drugs and Biological Products (December 2012)

- Draft Guidance: Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection -- Developing Direct-Acting Antiviral Drugs for Treatment (May 2016)

- Draft Guidance: Evaluation and Reporting of Age, Race, and Ethnicity Data in Medical Device Clinical Studies (June 2016)

ICH Guidances 🔗

- ICH, E7 Studies in Support of Special Populations: Geriatrics (June 24, 1993)

- ICH, E4 Dose Response Information to Support Drug Registration (March 1994)

- ICH, E5 Ethnic Factors in the Acceptability of Foreign Data (February 5, 1998)

- ICH, E11 Clinical Investigation of Medicinal Products in the Pediatric Population (July 20, 2000)

- ICH, M4 Common Technical Document for the Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (January 13, 2004)

Other Sources 🔗

- General Accounting Office: FDA Needs to Ensure More Study of Gender Differences in Prescription Drug Testing, GAO/HFD-93-17 (October 1992)

- Office of Management and Budget: Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity (June 9, 1994)

- Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Directive No. 15: Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity (October 30, 1997)

- Best Pharmaceuticals Act for Children of 2002 (Public Law 107-109) (February 4, 2002)

NIH PHS Cumulative Inclusion Enrollment Report Form 🔗

Footnotes 🔗

-

Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Directive No. 15 Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity (October 30, 1997), available at

https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/fedreg_1997standards ↩ -

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Public Law 111-148, Section 4302 (42 U.S.C. § 300kk) (March 23, 2010), available at https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CREC-2009-11-19/pdf/CREC-2009-11-19-pt1-PgS11607-3.pdf#page=127 ↩

-

HHS Implementation Guidance on Data Collection Standards for Race, Ethnicity, Sex, Primary Language, and Disability Status (October 31, 2011), available at https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/76331/index.pdf ↩

-

Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act (FDASIA), Public Law 112-144 (July 9, 2012), available at

https://www.congress.gov/bill/112th-congress/senate-bill/3187 ↩ -

FDA Action Plan To Enhance The Collection and Availability of Demographic Subgroup Data (August 2014), available at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/RegulatoryInformation/Lefislation/SignificantAmendmentstotheFDCAct/FDASIA/UCM410474.pdf ↩

-

CDISC standardized Study Data Tabulation Model (SDTM), Analysis Data Model (ADaM), Operational Data Model

(ODM), http://www.cdisc.org/system/files/members/standard/study_data_tabulation_model_v1_4.pdf ↩ -

Providing Regulatory Submissions in Electronic Format – Certain Human Pharmaceutical Product Applications and

Related Submissions Using the eCTD Specifications: Guidance for Industry (May 2015), available at

https://www.fda.gov/drugs/electronic-regulatory-submission-and-review/electronic-common-technical-document-ectd ↩ -

Providing Regulatory Submissions In Electronic Format - Standardized Study Data: Guidance for Industry (December 2014), available at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/.../Guidances/UCM292334.pdf ↩

-

63 FR 6854 (February 11, 1998) (codified at 21 CFR 312.33(a)(2) and 21 CFR 314.50(d)(5)) ,

https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-1998-02-11/pdf/98-3422.pdf ↩ -

Collection of Race and Ethnicity in Clinical Trials (September 2005),

http://www.fda.gov/downloads/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm126396.pdf ↩ -

The terms sex and gender have been used interchangeably in some FDA documents. However, according to a 2001 consensus report from the Institute of Medicine (Institute of Medicine, Committee on Understanding the Biology of Sex and Gender Differences. Exploring the Biological Contributions to Human Health: Does Sex Matter?), National Academy of Sciences, 2001, the terms have distinct definitions which should be used consistently to describe research results. Sex refers to the classification of living things, generally as male or female, according to their reproductive organs and functions assigned by chromosomal complement. Gender refers to a person’s self-representation as male or female, or how that person is responded to by social institutions based on the individual’s gender presentation. Gender is rooted in biology and shaped by environment and experience. Because of underlying differences in the statutes and regulations referenced in this policy, the terms “gender” and “sex” have both been used in this document in accordance with the source material referenced. ↩

-

21 CFR § 312.33(a)(2) (April 1, 2015). See also 21 CFR § 314.50(d)(5)(v) and (vi)(a) regarding demographic data submission in NDAs, available at http://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/textidx?SID=41aa69ac1cd29cf7eb1c3b24d764f310&mc=true&node=se21.5.314_150&rgn=div8 ↩

-

Draft Guidance: Evaluation and Reporting of Age, Race, and Ethnicity Data in Medical Device Clinical Studies (June

2016), available at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/GuidanceDocuments/UCM507278.pdf. Draft guidances are included for completeness only. As draft documents,

they are not intended to be implemented until published in final form. ↩ -

Center for Devices and Radiological Health Organization,

http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/OrganizationCharts/ucm347835.htm ↩ -

CBER Offices and Divisions, http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/OfficeofMedicalProductsandTobacco/CBER/ucm122875.htm ↩

-

CDER Offices and Divisions, https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/about-center-drug-evaluation-and-research/cder-offices-and-divisions ↩

-

Notice of Public Hearing: Action Plan for the Collection, Analysis, and Availability of Demographic Subgroup Data in Applications for Approval of Food and Drug Administration-Regulated Medical Products, 79 FR 42, 12134 (March 4, 2014), available at Federal Register. ↩

-

http://www.fda.gov/downloads/RegulatoryInformation/Legislation/SignificantAmendmentstotheFDCAct/FDASIA/UCM397391.pdf(April 2014) ↩

-

Institute of Medicine Workshop: Strategies for Ensuring Diversity, Inclusion, and Meaningful Participation in Clinical Trials (April 9, 2015), available at Institute of Medicine. ↩

-

FDA Public Meeting: Clinical Trials—Assessing Safety and Efficacy for Diverse Populations, 80 FR 210, 66909 (October 30, 2015), available at Federal Register. ↩

-

Improving the Collection and Use of Racial and Ethnic Data in HHS (December 1, 1999), available at HHS Report. ↩

-

On September 21, 2016, HHS issued the Final Rule on Clinical Trials Registration and Results Information Submission (42 CFR Part 11). When fully implemented, the rule will require the submission of race and ethnicity information with summary results information, if collected during the trial. Available at HHS Final Rule. ↩

-

E5 Guidance on Ethnic Factors in the Acceptability of Foreign Clinical Data, available at ICH E5 Guidance. ↩

-

NIH Revitalization Act of 1993 (PL 103-43) (June 10, 1993), available at NIH Revitalization Act PDF. ↩

-

NIH Revitalization Act of 1993 (PL 103-43), Subtitle B (June 10, 1993), available at NIH Revitalization Act Subtitle B. ↩

-

NIH Policy and Guidelines on The Inclusion of Women and Minorities as Subjects in Clinical Research (October 2001), available at NIH Guidelines. ↩

-

21 CFR § 312.33(a)(2), available at 21 CFR 312.33. ↩

-

21 CFR § 314.50(d)(5)(v) and (vi)(a) (October 2015). See also Integrated Summary of Effectiveness Guidance for Industry, available at FDA Guidance PDF. ↩

-

Under 21 CFR 314.101(d)(3), the Agency may refuse to file an NDA if it is incomplete because it does not contain information required by 21 CFR 314.50. Thus, if there is an inadequate evaluation for safety and/or effectiveness of the population intended to use the drug, including pertinent subsets, such as gender, age, and racial subsets, the Agency may refuse to file the application. See FDA's Manual of Policies and Procedures, Office of New Drugs, Good Review Practice: Refuse to File (October 10, 2013), available at FDA Policies PDF. ↩

-

FDA Report: Collection, Analysis, and Availability of Demographic Subgroup Data for FDA-Approved Medical Products (August 2013), available at FDA Report PDF. ↩

-

In June 2005, FDA approved BiDil, the first drug approved by the Agency to treat a disease in patients identified by race. The drug was approved for the treatment of heart failure in Black patients. The sponsor conducted two trials in the general population that failed to show a benefit but suggested a benefit of BiDil in Black patients. The company then studied the drug in 1,050 self-identified Black patients, and it was shown to be safe and effective. ↩

-

Huang SM & Temple R. 2008. “Is this the drug or dose for you? Impact and consideration of ethnic factors in global drug development, regulatory review, and clinical practice.” Clin Pharmacol Ther, 84: 287-294. ↩

-

Ramamoorthy A, Pacanowski MA, Bull J, and Zhang L. 2015. "Racial/ethnic differences in drug disposition and response: review of recently approved drugs." Clin Pharmacol Ther, 97: 263-273. ↩

-

Taylor S. 2002. “Skin of Color: Biology, Structure, Function, and Implications for Dermatologic Disease.” Journal of American Academy of Dermatology, 46: S41-62. ↩

-

Yan, Guofen, et al. 2013. "The Relationship of Age, Race, and Ethnicity with Survival in Dialysis Patients." Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 8(6): 953-961. ↩

-

Exner D, Dries D, Donamski M, and Cohn J. 2001. “Lesser Response to Angiotensin-Converting-Enzyme Inhibitor Therapy in Black as Compared with White Patients With Left Ventricular Dysfunction.” N Engl J Med, 344: 1351-1357. ↩

-

Yancy C, Fowler M, Colucci W, Gilbert E, Bristow M, et al. 2001. “Race and the Response to Adrenergic Blockade with Carvedilol in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure.” N Engl J Med, 344: 1358-1365. ↩

-

The terms used in this guidance to describe the various racial and ethnic groups are those used by OMB. ↩

-

Xie H, Kim R, Wood A, and Stein C. 2001. “Molecular Basis of Ethnic Differences in Drug Disposition and Response.” Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol, 41: 815-850. ↩

-

Carbamazepine Postmarket Drug Safety and Information (December 12, 2007), available at FDA Postmarket Drug Safety. ↩

-

Chung WH, Hung SI, Hong HS, Hsih MS, Yang LC, et al. 2004. “A Marker for Stevens-Johnson Syndrome.” Nature, 428: 486. ↩

-

Hung SI, Chung WH, Jee SH, Chen WC, Chang YT, et al. 2006. “Genetic Susceptibility to Carbamazepine-Induced Cutaneous Adverse Drug Reactions.” Pharmacogenetics and Genomics, 16: 297-306. ↩

-

Alfirevic A, Jorgensen AL, Williamson PR, Chadwick DW, Park BK, Pirmohamed M. 2006. “HLA-B Locus in Caucasian Patients with Carbamazepine Hypersensitivity.” Pharmacogenomics, 7: 813-818. ↩

-

Guidance for Industry: Clinical Pharmacogenomics: Premarket Evaluation in Early-Phase Clinical Studies and Recommendations for Labeling (January 2013), available at FDA Guidance PDF. ↩

-

Draft Guidance: Enrichment Strategies for Clinical Trials to Support Approval of Human Drugs and Biological Products (December 2012), available at FDA Draft Guidance PDF. ↩

-

NIH Policy and Guidelines on The Inclusion of Women and Minorities as Subjects in Clinical Research (Amended, October 2001), available at NIH Guidelines ↩

-

NIH PHS Inclusion Enrollment Report Form (March 25, 2015), available at NIH Grants PDF ↩

-

Providing Regulatory Submissions in Electronic Format – Certain Human Pharmaceutical Product Applications and Related Submissions Using the eCTD Specifications: Guidance for Industry (May 2015), available at FDA Guidance PDF ↩

-

Revision of M4E Guideline on Enhancing the Format and Structure of Benefit-Risk Information on ICH Efficacy – M4E(R2) (June 15, 2016), available at ICH M4E Guideline ↩

-

The ICH M4 eCTD document suggests specific kinds of demographic information to be collected as a part of a clinical trial but does not provide rigid specifications on how the data should be presented. For example, it notes that “if relative exposure of demographic groups in the controlled trials differs from the overall exposure, it may be useful to provide separate tables.” Choices on how best to summarize demographic data depend on the nature of the data to be conveyed. For some trials, it may be useful to show the distribution of one demographic characteristic within a second demographic (e.g., the age distribution of men and women enrolled in a set of controlled trials). ↩