Introduction 🔗

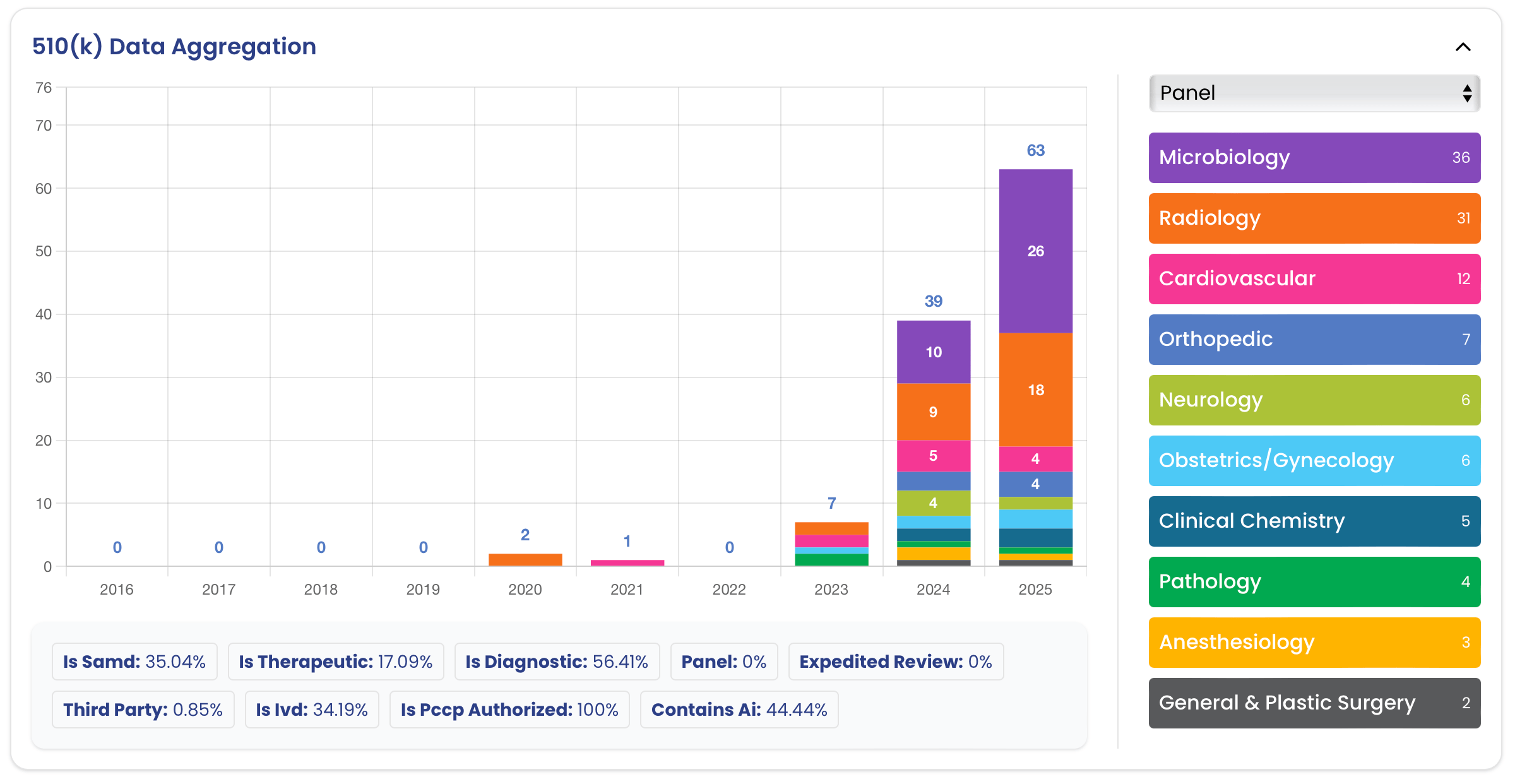

PCCPs, or Predetermined Change Control Plans, are a new regulatory tool that allow companies to “pre-clear” certain changes within a 510(k), De Novo, or PMA. While the unique regulatory challenges related to AI are what spurred FDA to develop this innovative approach, PCCPs can be used much more broadly. Here at Innolitics, we expect that PCCPs will become an increasingly important over time. The surge in their use since Congress provided FDA this statutory authority demonstrates this.

Best Practices 🔗

- Planning and Scope

- Consider doing a separate pre-sub just for the PCCP.

- Consider a standalone 510(k) submission just for the PCCP.

- Keep the number of changes to a minimum to enable an efficient review; a PCCP should not include a list of all modifications that a manufacturer may possibly make.

- If your PCCP covers multiple, independent changes, separate them in the documentation to make it easy to selectively remove particular changes.

- FDA is more cautious with new technologies and regulatory approaches, so expect to need to provide a lot of detail and precision in your PCCP; if the PCCP adds relatively little value to the device, it may not (yet) be worth pursuing.

- Submissions

- The PCCP should be discussed in the cover letter and the submission’s table of contents.

- Labeling should state that the device has an authorized PCCP.

About the Author 🔗

Hi, I’m David Giese, a Partner at Innolitics. I’ve wrote this article based on my real-world experiences bringing 35+ diagnostic medical devices onto the US market. I take pride in the in-depth articles I write, and appreciate feedback and questions. I’d love to connect on LinkedIn, where I post pragmatic tips about medical-device cybersecurity for more than 4k followers.

Basic 🔗

What is a PCCP? 🔗

A Predetermined Change Control Plan, or PCCP, describes planned changes that may be made to a device that would otherwise require another FDA submission. A PCCP for a device is reviewed as part of a 510(k), De Novo, or PMA.

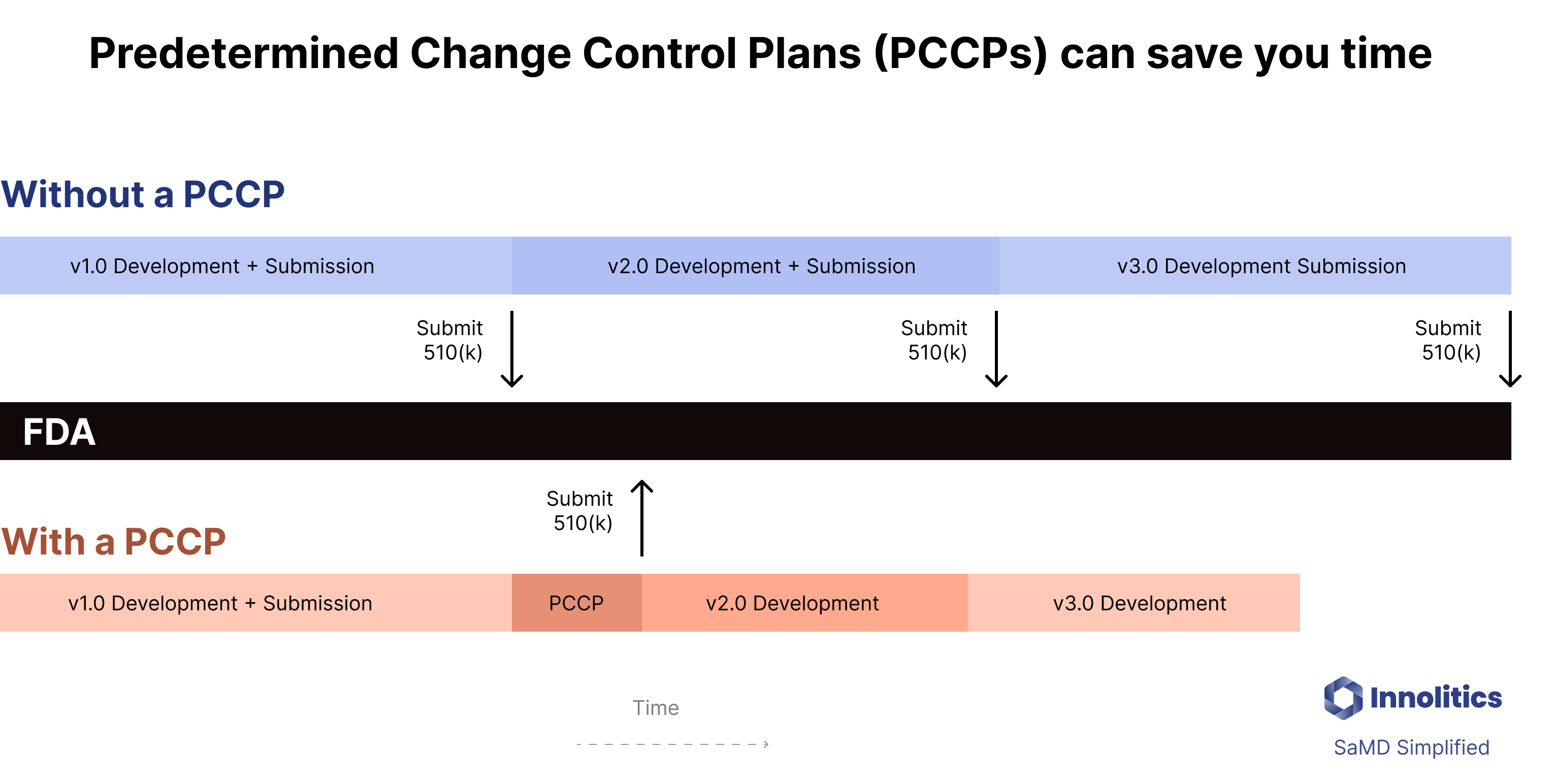

Why are PCCPs useful? 🔗

PCCP plans may allow you to avoid time-consuming and expensive regulatory submissions by pre-clearing your changes with FDA. If you have a PCCP plan you will have to do most of the work required for a 510(k), but you won’t need to wait the additional 60 - 120 days for the FDA to complete their review.

When can you use a PCCP? 🔗

The focus has been to use PCCPs to allow updates to AI/ML models, however, the underlying laws and regulations are quite broad. In fact, they have been used in several devices without AI/ML and even hardware only devices already. (See the examples section below for some creative uses of PCCPs.)

Here at Innolitics we’re still exploring possible use cases for PCCPs. We believe they may be used in a number of ways, including:

- To “pre-approve” upcoming software features that are well understood but haven’t been implemented. Doing a PCCP could allow you to get the software in front of the FDA sooner while you’re development team is finishing the remaining features.

- To “shelf” features of an SaMD device that aren’t performing well enough to be cleared yet aren’t important enough to delay the overall submission. In these cases, we think there may be a way to submit a PCCP to optimize the submission timeline.

That said, you can’t use PCCPs for several types of changes, including

- changes that would modify the intended use

- changes that would not actually require a new 510(k)

- changes that would break your substantial equivalence determination

- changes that aren’t thoroughly and clearly understood (as it will be impossible to provide a PCCP that is detailed enough).

How do you create and use a PCCP? 🔗

-

Background Reading

- Read this article and the relevant FDA guidance (see the “” question below).

- See what information you can glean from 510(k) letters and labeling of related devices that used PCCPs. (Checkout our 510(k) Search Tool.)

- If you are using an FDA product code that explicitly includes a PCCP, read the special controls in the founding De Novo. See the QVD example below.

-

Draft PCCP Documentation

- The documentation needed will depend on the type of PCCP. In general, we expect FDA to require similar documents to the ones described in the draft AI/ML PCCP guidance.

- Description of Modifications which will describe the types of changes that are allowed under the PCCP.

- A risk assessment of the PCCP.

- See the other questions for more details.

-

Consider a Pre-Sub

- Since PCCPs are so new, we suggesting using a Pre-Sub for all PCCPs.

- To have an effective Pre-Sub, we suggest having a detailed draft of the PCCP completed.

-

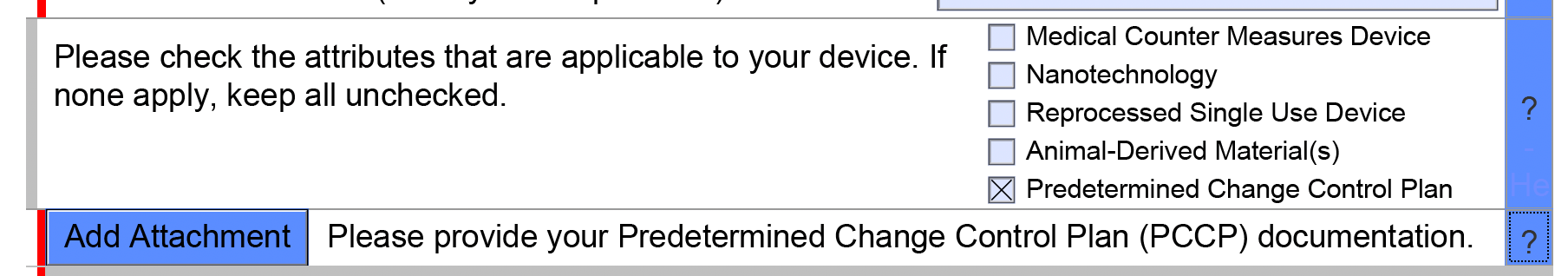

Finalize PCCP and add Marketing Submission eSTAR

- Finalize the documents, enter them into revision control in your QMS, and attach to the eSTAR (see screenshot below).

-

FDA Approval

- FDA will then review your marketing submission, including your PCCP.

- They may have you remove some changes or the entire PCCP from the submission.

-

Implement the PCCP

- Once a PCCP has been reviewed and established through a marketing submission, the PCCP is considered part of the marketing authorization.

- You can then make changes consistent with the PCCP (i.e., with the Description of Modifications) assuming they are implemented in

What have PCCPs been used for so far? 🔗

A major use of PCCPs is to make it easier to update AI/ML functions, however, PCCPs have already been used for a number of other situations:

- Adding support for new hardware input sources to SaMD

- Adding new genetic variants to IVDs

- Making breakpoint changes to antiobiotic susceptibility testing (AST) platforms (there is a finalized guidance for this already)

See the examples section below for in depth explorations of some of these.

Can you use a PCCP for a De Novo? 🔗

Yes. PCCPs have been used in De Novos classification requests already.

For example, see DEN220063 which established the QVD product code “

See the examples section for a particular De Novo and product code that was established.

Can you add a PCCP when FDA requests additional information? 🔗

No. Based on our experience with FDA, it has been required that you include the PCCP in your original submission. You can’t add a PCCP after you’ve already submitted a 510(k), for example.

Do you really need a new product code for devices with a PCCP? 🔗

In the early days of PCCP plans, we had FDA suggest to us that devices with a PCCP would not be considered substantially equivalent to devices without a PCCP. As a result, new types of devices with PCCPs would require a De Novo classification request to create a new product code.

However, it seems clear this is not the case as there are several cleared 510(k)s for devices with PCCPs whose predicts did not have PCCPs.

Does FDA require you to implement changes planned in a PCCP? 🔗

No. The manufacturer is not obligated to make any changes described within a PCCP.

Can you edit a PCCP after it has been authorized? 🔗

No.

What would happen if you make changes that don’t comply with a PCCP? 🔗

FDA may catch the inappropriate changes in an audit.

FDA also will review marketing materials from your website and if they see something inappropriate they will ask to see your change control documentation for the changes.

If FDA deems the changes were inappropriate, they may recall the updated version of the software and issue a warning.

Where can I learn more about PCCPs? 🔗

- Videos

- Statutes

- Regulations

- Guidance

- Marketing Submission Recommendations for a Predetermined Change Control Plan for Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (AI/ML)-Enabled Device Software Functions (August 2025)

- Draft Predetermined Change Control Plans for Medical Devices (August 2024)

- Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test (AST) System Devices – Updating Breakpoints in Device Labeling (September 2023)

Strategy 🔗

Can you include multiple changes in a single PCCP? 🔗

Yes. However, an FDA reviewer suggested to keep the changes split apart so that it would be easy for FDA to selectively reject certain changes but not others.

Also, “FDA recommends that a PCCP include only a limited number of modifications that are specific, and that can be verified and validated.”

Does FDA allow PCCPs for site-specific fine-tuning? 🔗

Yes, one of the use-cases of a PCCP is to allow for site-specific tuning.

Here’s a PCCP that was cleared for site.

Also, see this example from the FDA guidance regarding ventilator settings. the example from the FDA guidance:

Submissions 🔗

What content goes into a PCCP? 🔗

A PCCP should contain the following sections:

- A description of modifications

- The modification protocol

- An impact assessment

Do we need to disclose to our users that our device has a PCCP? 🔗

Yes. The labeling should note the PCCP and its scope.

AI PCCPS 🔗

History 🔗

How long have PCCPs been available? 🔗

They have been available since December 2022, so they are relatively new.

FDA is always more cautious with new technologies and regulatory approaches, so expect the admin overhead to be higher until more guidance has been published.

Why did FDA request additional authority to support PCCPs? 🔗

In September 2022 FDA published their final report for their Pre-Cert Pilot program. In this report they state (emphasis mine):

FDA felt that the older regulatory approach with 510(k)s was not fast enough to allow for software innovation. Congress gave FDA authority to administer PCCPs in December 2022.

FDA reviews a lot of marketing submissions. They would like to spend their time focused on the high-risk, new technologies that require their detailed oversight. This is the same reason they set up the third-party review program.

Examples - Product Codes 🔗

QVD - Radiological machine learning-based quantitative imaging software with PCCP 🔗

The QVD product code is (as best we are aware) the first product code created specifically for PCCP plans. It falls under the 892.2055 regulation and has the following description:

As is often the case, a lot of the juicy details are found in the De Novo submission that established the product code. Here are the special controls required from the De Novo. I suspect new product codes for other types of PCCP plans will contain similar controls.

- Design verification and validation must include:

- A detailed description of the image postprocessing algorithms, including a detailed description of the algorithm inputs and outputs, each major component or block, and algorithm limitations.

- Detailed description of training data including detailed annotation methods and important

cohorts (e.g., subsets defined by patient demographics, clinically relevant confounders, and subsets defined by image acquisition characteristics). - Performance testing protocols and results that demonstrate that the underlying algorithms function as intended. The performance assessment must be based on objective performance measures (e.g., error metrics, Bland-Altman plots, dice similarity coefficient (DSC), Hausdorff distance, sensitivity, specificity, predictive value). The test dataset must be independent from data used in training/development and contain sufficient numbers of cases from important cohorts (e.g., subsets defined by clinically relevant confounders, effect modifiers, concomitant diseases, and subsets defined by image acquisition characteristics) such that the performance estimates and confidence intervals of the device for these individual subsets can be characterized for the intended use population and imaging equipment.

- Software verification, validation, and hazard analysis.

- As part of the design verification and validation activities, you must document the planned device modifications of the quantitative imaging software, and the associated methodology for the development, verification, and validation of modifications made consistent with the performance requirements in the plan.

- As part of the risk management activities, you must identify and assess the risks of the planned modification(s) and identify corresponding risk mitigations.

- Labeling must include:

- A detailed description of the patient population for which the device was validated;

- A description of the intended user and expertise needed for safe use of the device;

- A detailed description of the device inputs and outputs;

- A detailed description of compatible imaging hardware and imaging protocols;

- A detailed summary of the current performance of the device and a summary of the performance testing conducted to support safe and effective use of the device including test methods, dataset characteristics (including demographics), testing environment, results (with confidence intervals), and a summary of sub-analyses on case distributions stratified by relevant confounders;

- A description of situations in which the device may fail or may not operate at its expected

performance level (e.g., poor image quality or for certain subpopulations), as applicable; - Labeling related to the predetermined change control plan (PCCP), including:

- A statement that the device has a PCCP;

- A description of modification(s) implemented for quantitative imaging and supporting

algorithms, including a summary of current performance, associated inputs, validation requirements, and related evidence; and - A version history, a description of how device modification(s) will be implemented, and a description of how users will be informed of device modification(s) made in accordance with the PCCP.

In addition, this is a prescription device and must comply with 21 CFR 801.109.

Examples - Creative Uses of PCCPs 🔗

Natural Cycles - Adding New Temperature Measuring Devices 🔗

Natural Cycles is Software as a Medical Device (SaMD), intended for women 18 years and older, to monitor their fertility. Natural Cycles can be used for preventing a pregnancy (contraception) or planning a pregnancy (conception). It was founded by particle physicist Elina Berglund (who was on the team that discovered the Higgs Boson).

In 2017, Natural Cycles submitted a De Novo classification request and created the PYT product code for “Device, Fertility Diagnostic, Contraceptive, Software Application”.

In 2020, they submitted a 510(k) to add support for the Ōura smart ring. As part of the submission they did a clinical study with 40 women and compared the effectiveness of their algorithm with the original oral thermometer with the Ōura ring.

In 2023, they submitted another 510(k) for using the Apple Watch as a temperature source.

In 2024, they submitted a 510(k) for their device (K241006) which did not include any changes to their software, but only included the proposed PCCP. The PCCP is meant to obtain authorization from FDA to add more wearables providing temperature as an input to the Natural Cycles fertility algorithm in the future without requiring additional 510(k)s.

This seems like a great use case for a PCCP. The company had done two studies already and understood how to evaluate adding new temperature-measurement devices. Furthermore, it was not possible to add support for new devices using a letter-to-file since the new devices do introduce new questions of safety and effectiveness. Furthermore, it is clear they were able to define very precise acceptance criteria and KPIs for use when evaluating new hardware devices like the Apple Watch and Ōura smart ring:

Here is a list of KPIs that are used to evaluate the new hardware devices:

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs):

- Positive Percent Agreement (PPA) to assess product safety and contraceptive effectiveness, i.e., how often the user is exposed to a pregnancy risk because of a wrongly flagged green day in the fertile window.

- Fraction of green days assigned by the fertility algorithm over the total number of days for a given cycle, then averaged over all cycles.

- Day to day variability (std) – the standard deviation of the daily temperature values.

- Ratio between the temperature phase separation and the standard deviation, i.e., the temperature difference between the pre-ovulatory and post-ovulatory phases of the menstrual cycles.

- Detected ovulations – the fraction of cycles with positive LH where ovulation is detected by the Natural Cycles algorithm using the temperatures from the device under consideration as input.

- Ovulation resolution – fraction of cycles with positive LH and ovulation detected, where ovulation is detected within two days from the LH-only ovulation day.

Specifications

| KPI | Specification |

|---|---|

| Std | CI upper bound ≤ 0.234 |

| Ratio | CI lower bound ≥ 2.04 |

| Ovulation detection | CI lower bound ≥ 85.5% |

| Ovulation resolution | CI lower bound ≥ 76.1% |

| PPA | CI lower bound ≥ 96.5% |

| Fraction of green days | No more than 2 additional red days per cycle compared to the oral thermometer |

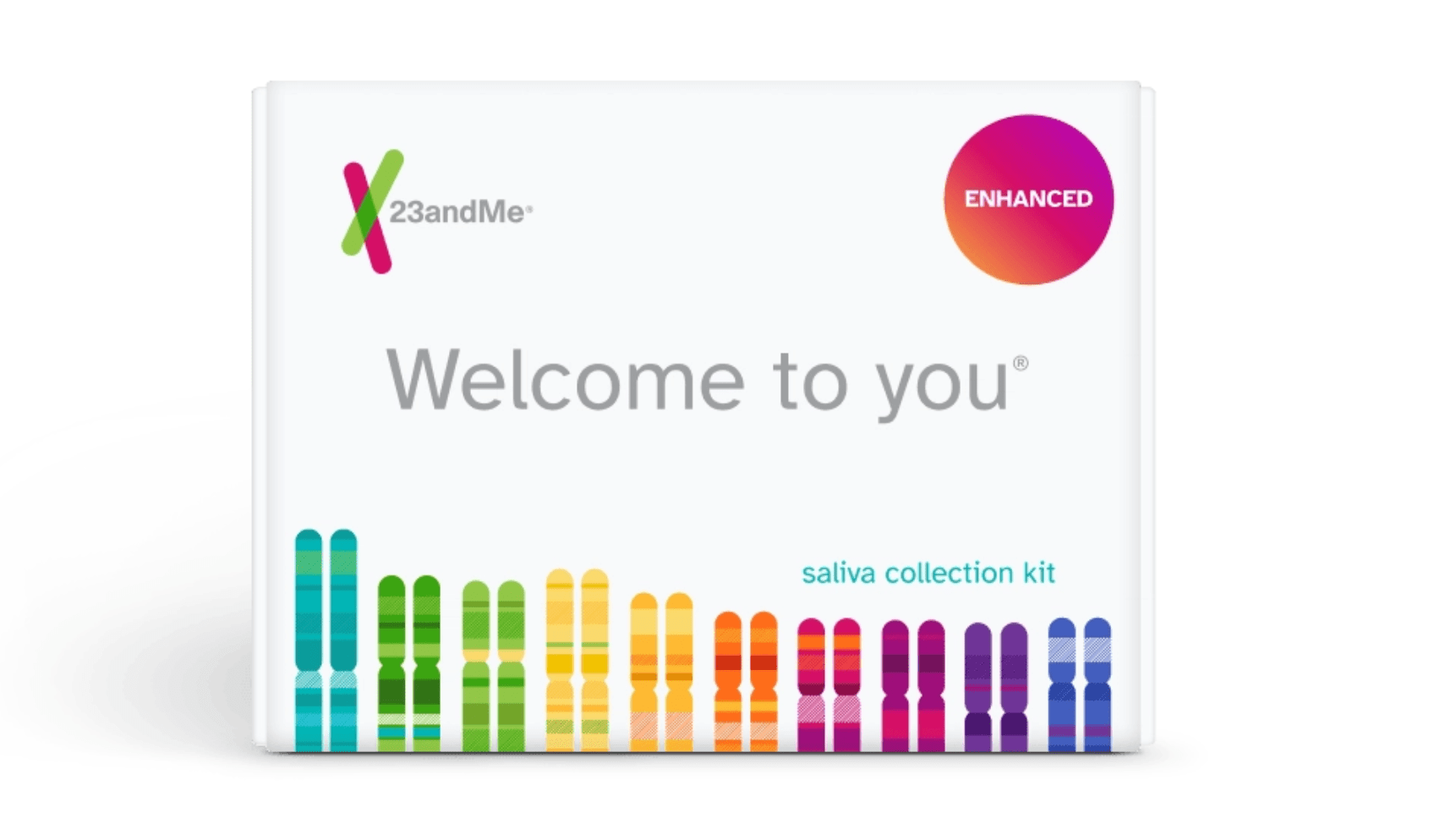

23andMe Personal Genome Service (PGS) Genetic Health Risk Report 🔗

23andMe does genetic testing for health and ancestry purposes. They have an interesting FDA history that reaches back over a decade. More recently, they provide an example of using a PCCP for a non AI/ML purpose.

In 2013, 23andMe received a warning letter from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to discontinue marketing its health-related genetic tests in the United States.

In October 2015, after two years of work with FDA, they were granted a De Novo (DEN140044) for “the detection of the BLMAsh variant in the BLM gene from saliva collected using an FDA cleared collection device (Oragene DX model OGD-500.001).”

In April, 2017, they were granted authorization for a genetic health risk report for 10 diseases and conditions.

In March, 2018, 23andMe received the first-ever FDA authorization for a direct-to-consumer genetic test for cancer risk. The authorization allows 23andMe to provide customers, without a prescription, information on three genetic variants found on the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes known to be associated with higher risk for breast, ovarian and prostate cancer.

In August, 2023, they were cleared for 41 more BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic variants and they established a PCCP for reporting additional variants and associated cancer risk information to the report.

Details about their PCCP plan may be found both in their 510(k) letter and also in their labeling:

Although details aren’t included, it is clear that the nature of the planned changes and the controls for the changes must be specified in detail.

Revision History 🔗

| Date | Changes |

|---|---|

| 2024-08-07 | Initial Version with just the basic questions. |