Introduction 🔗

EDIT: You are allowed to say "ideally" only if you follow it up with "realistically". However, this takes some skill to build up, so first keep the rules simple and just never say "ideally". Once you've mastered this skill, you can then say "ideally", but only with the condition of saying "realistically" afterwards.

This phrase came from a client call.

I answered a question in a way that felt careful, qualified, and non-committal. The kind of answer that sounds reasonable in a vacuum, but doesn't actually help a decision-maker choose.

The client said: "You are doing the ‘consultant thing’ again."

No further definition. No debate. Somehow that got the point across with insane signal-to-noise. It meant: I don't need the ideal world. I need a recommendation in the real world.

That line stuck with me because they were right. The intent wasn't bad. The effect was.

And if you build regulated medical devices, this shows up constantly and is more broadly applicable to any consultative field like law, accounting, statistics, and medicine.

Stop Using "Ideally" 🔗

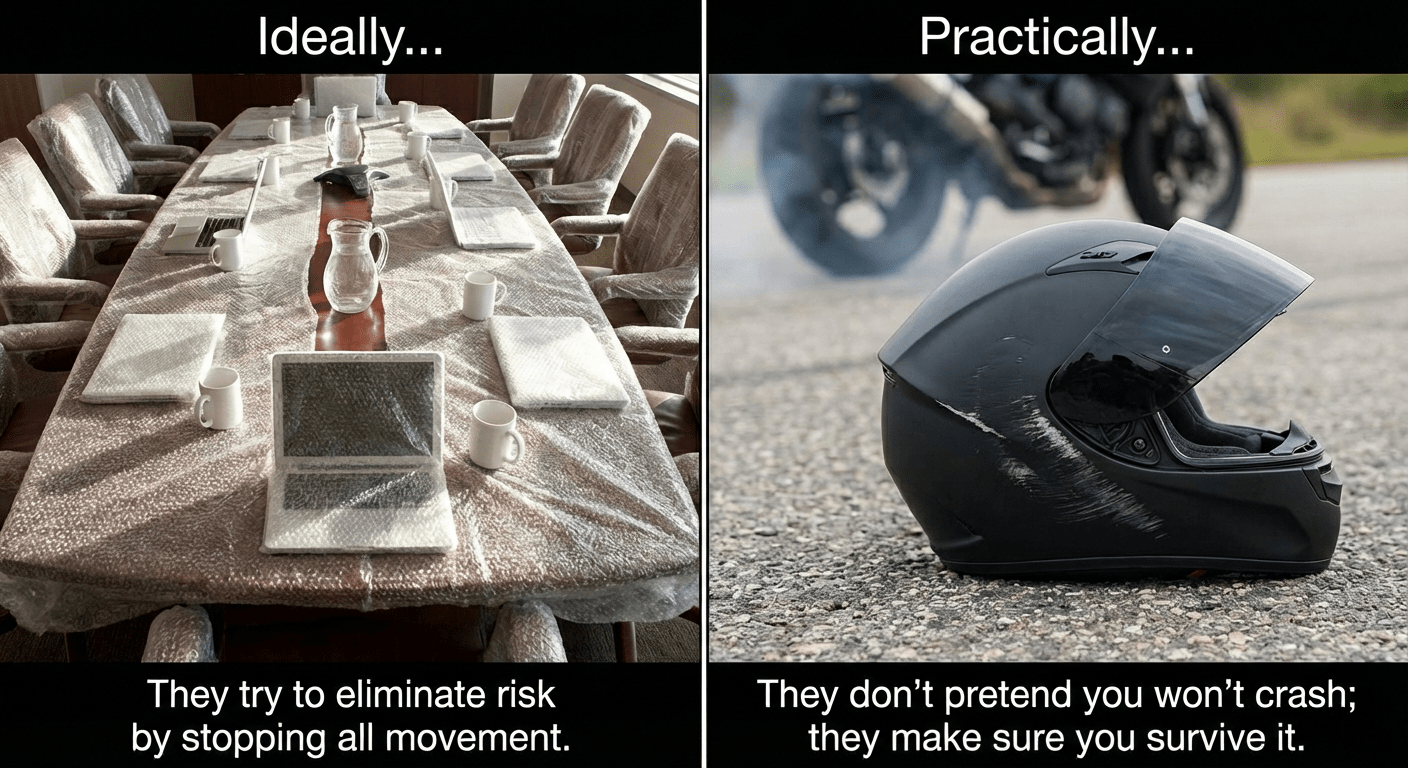

There's a word that sneaks into consultant speak when someone wants to sound helpful without committing to anything: ideally.

Ideally you'd rebuild the whole system. Ideally you'd hire a hundred more people. Ideally you'd adopt a new platform, redo the process, retrain everyone, and rewrite the SOPs.

Ideally… you would have infinite money and infinite time.

It sounds thoughtful but It's also often useless.

I'm not talking about genuine long-term vision. I'm talking about the move where "ideally" becomes a shield. It lets someone recommend the cleanest, most expensive, least-likely-to-happen version of a solution. Then they get credit for being "strategic," while the client is left holding a bag of unrealistic options.

Why "ideally" lands so badly 🔗

Clients don't pay for a tour of the perfect world. They pay for decisions they can actually make.

When you tell someone what they should do "ideally," you're often skipping the part that matters:

- What can we do with the team we have?

- What can we do with the budget we have?

- What can we do in the time we have?

- What would you do in our situation?

Without those constraints, your recommendation is not a plan. It's a daydream.

And daydreams have a cost. They burn meeting time and muddy strategies.

A better move: give the real recommendation first 🔗

If you're going to talk about the ideal state, fine. But start with what you'd actually do if you owned the outcome.

Here's a pattern that works:

- Recommendation: What I would do next week.

- Why: The constraint you're optimizing for.

- Tradeoffs: What you're not doing, and what risk that creates.

- Ideal (optional): What you'd build if constraints changed.

One sentence can do the job:

"Given your budget and timeline, I'd do X now, accept Y risk, and revisit Z when you have capacity, however, for educational purposes, if budget and timeline was not an issue, I would do ABC."

"Ideal" should be a fork in the road, not the main road 🔗

The ideal version is only useful if it helps someone choose.

Use it to:

- educate the client about why you are asking them to take a particular direction

- offer consolation that it could be a lot worse

- clarify what the long-term target looks like

- explain why a short-term compromise is reasonable

- define what needs to be true to upgrade later

Don't use it to avoid making a call.

The litmus test 🔗

Before you say "ideally," ask yourself one question: If they can't do the ideal thing, what should they do instead?

If you don't have a crisp answer, you're not done thinking.

Clients don't need more ideals. They need fewer, sharper decisions.

Where this shows up in AI medical device work 🔗

AI medical device projects attract "ideally" talk because there are so many knobs you could turn. Study design is the main one.

Sample size: the "ideally" trap 🔗

Ideally: run a large, fully powered prospective, multi-site study with clean prevalence, balanced subgroups, and narrow confidence intervals everywhere.

Reality: you have a budget, a timeline, and a dataset that exists in the real world.

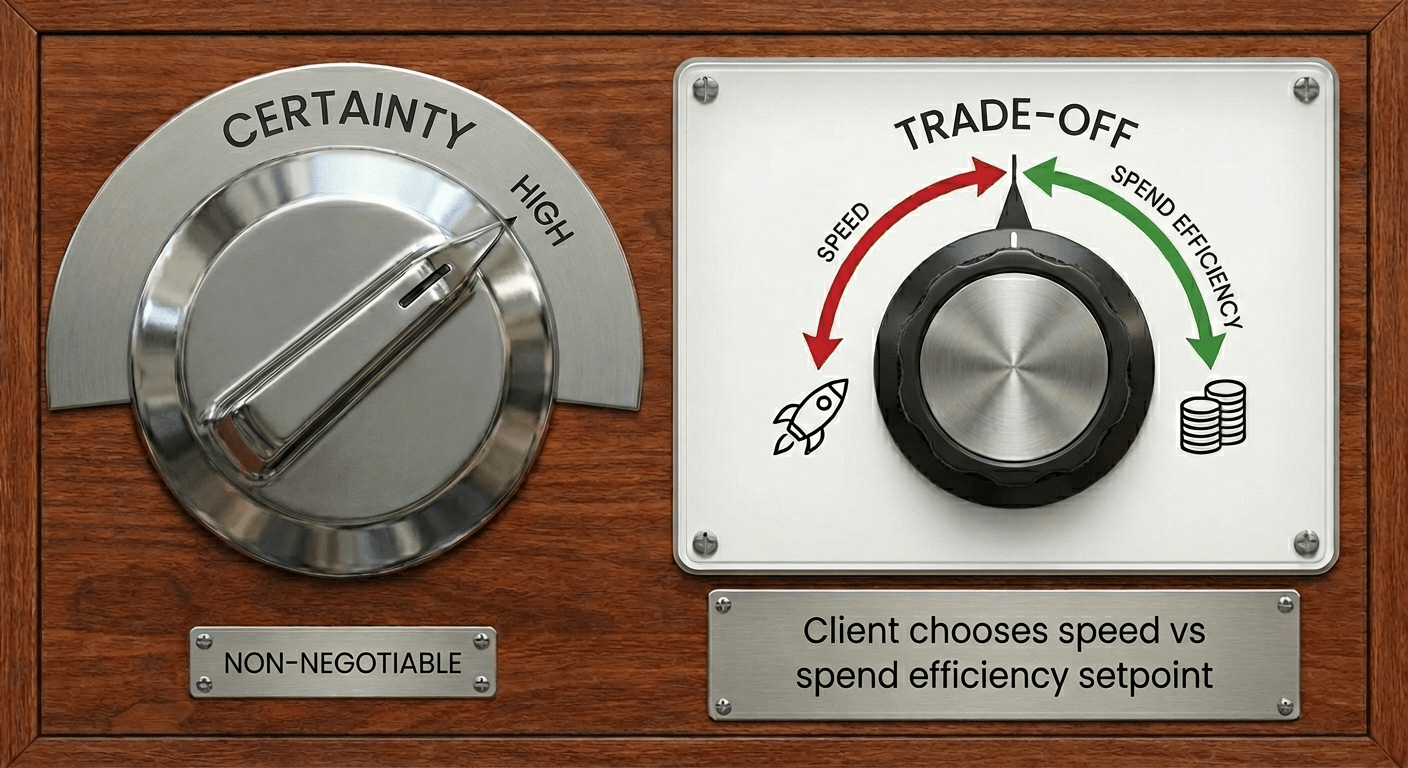

What clients need is not the ideal. They need the calibration point.

- If the client is optimizing for cost, you keep the same quality bar, but you pay for it with time:

- it can take longer to find the right data sources and get access

- contracting and data-use negotiations can drag

- reader hiring and scheduling can stretch (and good readers aren't cheap)

- the project runs more sequentially, with fewer parallel workstreams

- If the client is optimizing for speed, you keep the same quality bar, but you pay for it with money and coordination:

- you run more workstreams in parallel (and accept the overhead)

- you might pay for duplicate work streams to hedge the risk of any one of them failing

- you pay for faster data access and faster legal review when possible

- you lock in reader availability early, often at a premium

- you staff more heavily to keep the pipeline moving and avoid gaps

- you make decisions faster, with tighter timeboxes and fewer rounds of debate

The consultant's job is to find that budget vs speed setpoint, then make every design choice match it. Not to recite the ideal as a performance.

Adjudication strategy: perfect labels vs usable labels 🔗

Ideally: multiple expert readers, blinded, independent reads, consensus adjudication, and a pristine reference standard for every case.

Reality: reader time is expensive, disagreement is common, and not every endpoint is adjudicatable to perfection.

So you decide:

- Where adjudication actually reduces risk (the borderline cases that swing the ROC).

- Where it is waste (cases where everyone agrees, or where the endpoint is objective).

- Whether you need dual reads on everything, or dual reads on a subset with targeted adjudication.

Clients often assume "more adjudication" is always better. It isn't. It's better when it changes your answer.

Data curation and subgroup coverage: infinite completeness vs decision-relevant completeness 🔗

Ideally: every scanner, every site, every demographic subgroup, every weird edge case, evenly represented.

Reality: you will run out of money before you run out of edge cases.

The calibration point is deciding what you must cover because:

- FDA will care.

- A competitor has that claim.

- Your intended use depends on it.

Everything else becomes a risk you name explicitly and plan to mitigate later.

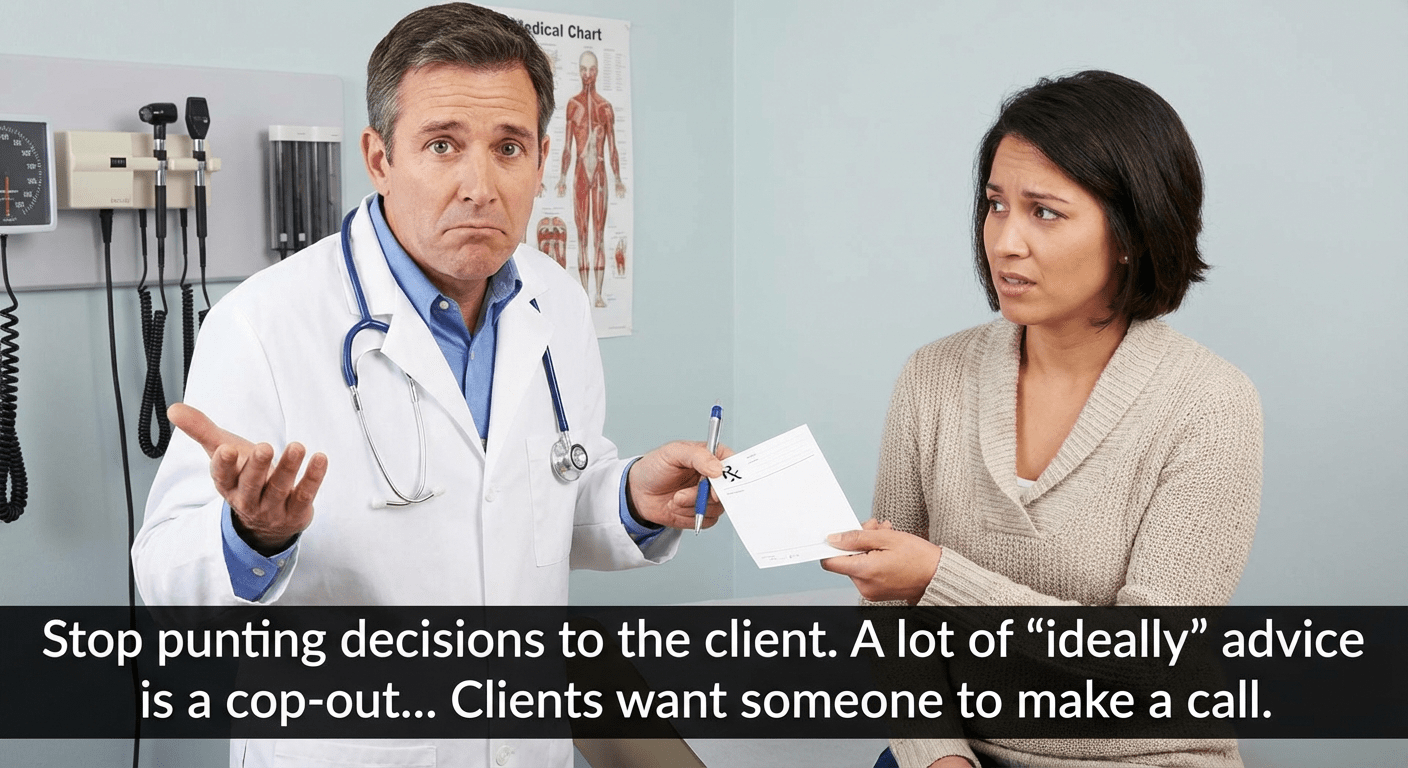

Stop punting decisions to the client 🔗

A lot of "ideally" advice is a cop-out because it pushes the uncomfortable part onto the client.

Clients are hiring a consultant precisely because they don't know where the calibration point should be. They want someone to ask the hard questions, make tradeoffs explicit, and make a call.

And here's the uncomfortable truth: the risks of not doing the ideal thing are often unquantifiable and subjective.

You usually can't say "this shortcut adds 17% more risk" with a straight face. Anyone who pretends they can is either guessing or hiding the assumptions.

So the honest job is to do two things at once:

- Name the risk in plain language.

- Tie that risk to a concrete consequence (patient safety, label claim, time-to-market, rework, reputation).

Then you give a recommendation that matches the client's setpoint.

Educate without confusing 🔗

Teaching clients what "ideal" looks like can be useful. The failure mode is when "ideal" becomes the main event.

A cleaner approach:

- Start with the recommendation you would actually execute.

- Describe the ideal as the ceiling and the direction, not the plan.

- Explain what needs to be true to justify moving toward it.

The real harm: spending money to appease uncertainty 🔗

When a consultant won't stick their neck out, the client still has to choose.

So they do the predictable thing. They spend extra money on process and "best practices" because it feels safer than making a judgment call.

It isn't safer. It's just expensive, slower, and often fatal for a medical device company in today’s hyper-competitive landscape.

Professional maturity: craft is good, restraint is better 🔗

I know everyone wants to be proud of their craft. People want to be proud of what they ship.

But sometimes the best outcome for the client involves a little self-sacrifice.

It means suppressing the urge to over-engineer so you can deliver what is good enough and defensible, instead of what is ideal.

That's not lowering the bar. That's choosing the right bar.

A simple rule helps:

- If you mention the ideal, you must also give the recommendation you'd actually run.

And if you catch yourself wanting to say "ideally" just to demonstrate expertise, don't.

Replace it with:

- "Here's what I'd do with your constraints."

- "Here's what we're trading off."

- "Here's what would need to be true before I'd recommend the fancier option."

This isn't just a consulting problem 🔗

This pattern shows up everywhere, including in specialists I hire myself.

Legal: chasing "risk-free" contracts 🔗

The "ideal" pitch: a contract that eliminates every possible risk.

The reality: there is no risk-free contract.

If you try to write one, two things usually happen:

- The contract becomes so one-sided the other side won't sign.

- Or both sides end up in an expensive review spiral, arguing over edge-case language that doesn't change the business outcome.

What you often need instead is a clear calibration point:

- What risks are truly non-negotiable (for example, confidentiality, IP ownership, and a clean exit).

- What risks are acceptable given deal size and urgency.

- What level of review is proportional to the dollars at stake.

A good lawyer helps you pick that line, then keeps the deal moving.

Biostatistics: chasing marginal power 🔗

The "ideal" pitch: push sample size until the study is maximally powered.

The reality: there's a point where you're paying a lot for very little risk reduction.

More power can be worth it when it changes a regulatory story, a label claim, or a business decision.

But the last increments of power can also be a vanity project. It inflates cost and timeline without changing the decision you need to make.

A good biostatistician translates options into consequences:

- What do we gain if we increase sample size?

- What do we lose in time and budget?

- Does it change the call we can make, or just make the spreadsheet look nicer?

CPAs: optimizing past the point of materiality 🔗

The "ideal" pitch: track everything, document everything, and engineer the tax position so it is bulletproof.

The reality: tax and accounting live in a world of thresholds, judgment calls, and materiality.

If your CPA treats every issue like a five-alarm fire, you get predictable outcomes:

- Your finance team spends weeks chasing tiny classifications and receipts.

- You pay for endless memos and reviews.

- You still don't get a zero-risk outcome, you just get a bigger bill.

A better CPA conversation sounds like:

- "What's the materiality threshold for this company?"

- "What's the worst-case downside if we take a reasonable position here?"

- "Is this worth the extra fees and time, or are we polishing?"

The point is not to ignore risk. It's to spend your attention where it matters.

Cybersecurity consultants: checklists vs threat-driven security 🔗

The "ideal" pitch: implement every best practice, buy every tool, and close every finding no matter how small.

The reality: you can spend forever on controls that don't match your actual attack surface.

Common examples:

- Treating a device with a narrow interface like it needs enterprise SOC-grade everything.

- Obsessing over certifications and buzzwords, instead of realistic threat scenarios.

- Generating a mountain of findings without a clear path to closure.

A real cybersecurity consultant starts with the threats:

- What are the crown-jewel assets (PHI, keys, update pipeline, clinical availability)?

- What are the plausible attack vectors in the real environment of use?

- What controls actually buy down risk for those vectors?

For CEOs, Leaders, and Executives: how to prevent the "consultant thing" 🔗

If you want real advice, you have to make it safe for your team and your consultants to give it.

1) Make it explicit: you own the decision 🔗

Tell your team and your consultant this up front:

- "I'm accountable for the decision."

- "I want you to quantify the risks as best you can and recommend a path."

- "You won't be punished for a reasonable call that doesn't work out."

This matters because most conservative, over-complicated advice is self-protection. People give you the safest-sounding option because they're optimizing for blame avoidance, not outcomes.

Your job is to remove that incentive.

What to ask for instead:

- A recommended plan.

- The top risks, stated plainly.

- The mitigations.

- The triggers that would cause you to change course.

If someone can't do that, they're not managing risk. They're hiding behind it.

Are you getting advice, or the “consultant thing”? 🔗

A real consultant does not hide behind "ideal." A real consultant makes a call.

Here are a few signs you're getting real advice.

They recognize their advice might not be popular with their peers.

- They are able to elucidate what their peers think and why they think it

- However, they are able to think outside their lane and understand how the larger system works to know the answer is not always black and white

They can give you an executable plan, not a perfect one.

- You leave the meeting knowing what happens next week.

- They can say what they would do with your current team and budget.

They can state tradeoffs without drama.

- They tell you what you're buying when you spend more.

- They tell you what you are accepting when you move faster.

They put uncertainty on the table, without pretending it's math.

- They can't always quantify risk, but they can name it clearly.

- They tie it to consequences you care about (time-to-market, claims, rework, reputation).

They don't inflate scope to feel important.

- They stop doing work that isn't buying certainty.

- They push back when you ask for busywork that won't change the decision.

They don't outsource judgment to you.

- They ask questions to find your calibration point.

- Then they recommend a path and own it.

And here are red flags that you're paying for the "consultant thing":

- Everything is framed as "ideal," and the practical option is treated like a sin.

- Every answer is "it depends," but nothing ever resolves.

- They propose gold-standard process because they won't take responsibility for a recommendation.

- Your team spends more time feeding the consultant than executing the plan.

If you feel like you're funding complexity instead of buying decisions, you should probably start looking for another consultant.

Conclusion: get a second opinion 🔗

If you're a CEO or decision-maker and you have that nagging feeling your consultant is doing the "consultant thing", saying "ideally" a lot, and leaving your team with more work than clarity, trust that instinct.

You don't need a new pile of best practices. You need a clear recommendation that matches your speed vs spend setpoint, without sacrificing certainty.

If you want a second opinion, reach out to Innolitics.

We help teams building AI software as a medical device make defensible decisions on:

- regulatory strategy

- clinical and performance study design

- cybersecurity

- engineering scope and execution

Sometimes the fastest way to de-risk a plan is a one-hour conversation with someone who will actually make a definitive call with your best interests in mind.