Introduction 🔗

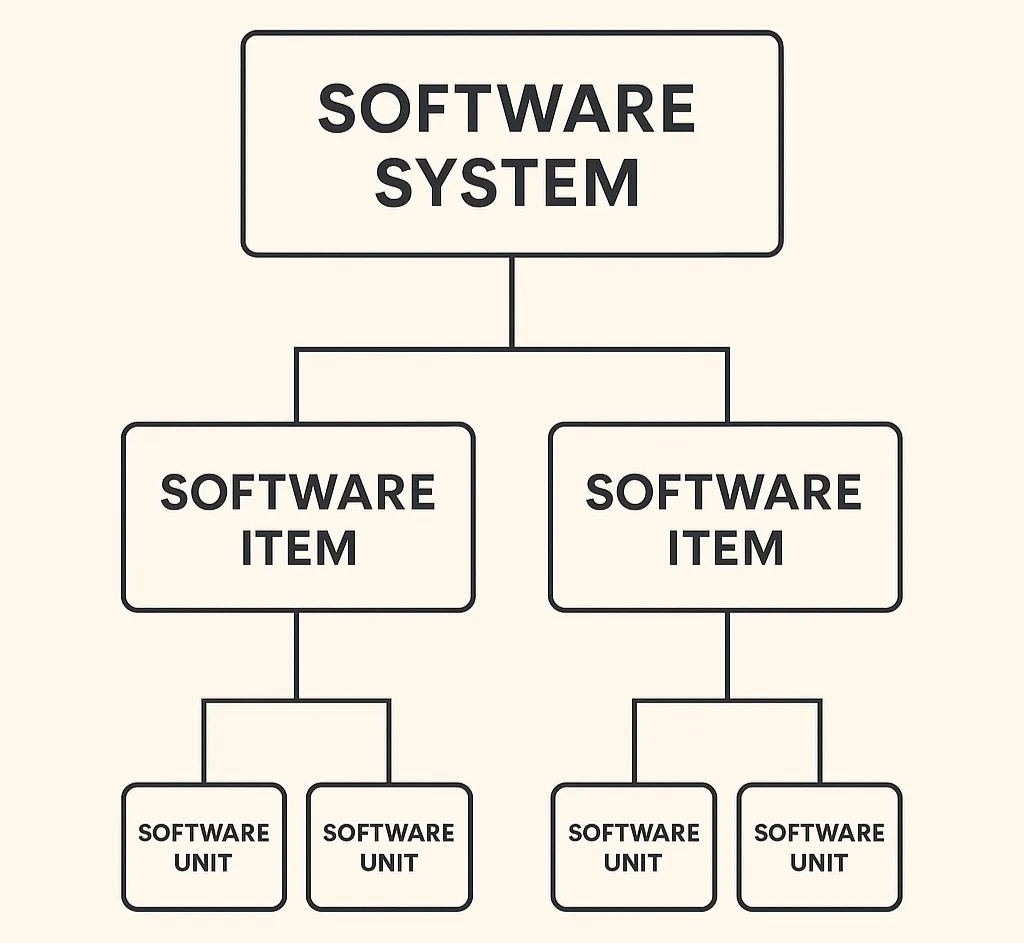

When FDA reviewers or software standards like IEC 62304 refer to system items, they’re talking about the conceptual building blocks that make up your software system—not necessarily the same thing as code modules or files.

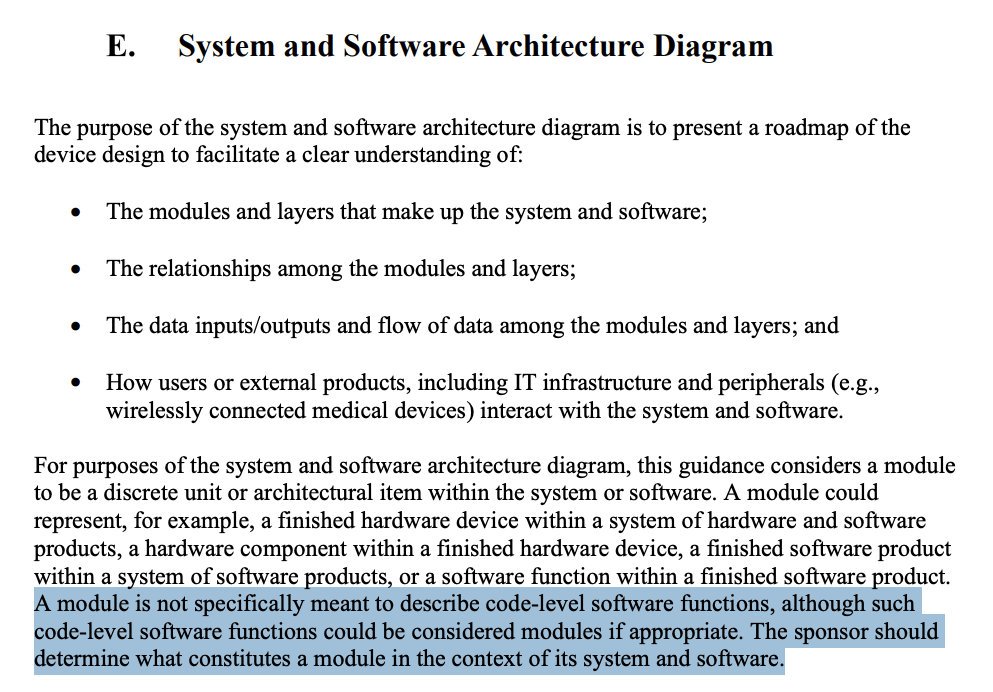

In FDA’s 2023 Guidance “Content of Premarket Submissions for Device Software Functions”, the system and software architecture diagram is described as a way to “present a roadmap” of the software’s major components (often called modules or items), their relationships, and data flows. FDA leaves it up to the manufacturer to define what a “module” or “item” means in context, explicitly stating that “a module is not specifically meant to describe code-level software functions”.

Similarly, IEC 62304 defines a software item as “any identifiable part of a computer program.” A software unit is simply a software item that is not further subdivided. This flexibility allows manufacturers to define decomposition based on the product’s architecture and risk, not on the folder structure of the codebase.

In practice, system items (or software items) are the conceptual elements (e.g., algorithms, services, interfaces, databases, communication layers, UI components, etc.) that collectively realize your software’s intended use. Their main purpose in documentation is to help reviewers understand how your software achieves safety and effectiveness, not to document how every file or class is written.

Why this Question Matters 🔗

Teams often assume their architecture diagram must exactly match their repository layout. That assumption bloats submissions, slows reviews, and obscures what FDA actually cares about: how your software achieves its intended use safely and effectively, and how you’ve tested it.

What FDA Asks For (And What It Doesn’t) 🔗

Purpose of the Architecture Diagram 🔗

FDA says the system and software architecture diagram should “present a roadmap” of modules/layers, their relationships, and data flows, and how users/external systems interact.

Not a Code Map 🔗

In FDA’s guidance on the content of a software submission, FDA explicitly notes: “A module is not specifically meant to describe code-level software functions… The sponsor should determine what constitutes a module in the context of its system and software.”

Use Multiple Diagrams and Tailor Detail 🔗

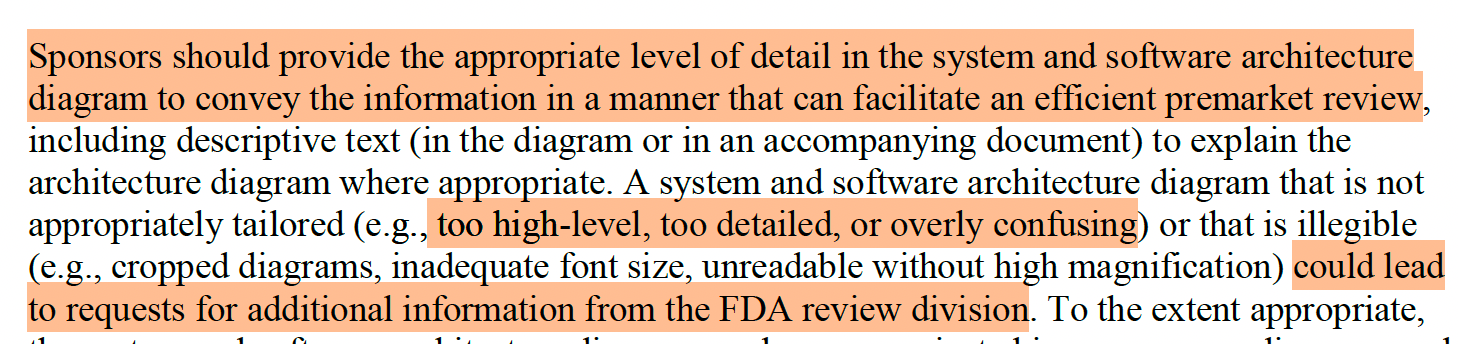

FDA encourages using one or more diagrams (static, dynamic/state, cybersecurity, etc.) at the level of detail that facilitates an efficient review—too high-level or too granular can trigger questions.

Your “modules” and “layers” can be conceptual building blocks that communicate safety-relevant structure and interfaces; they need not mirror packages, folders, or microservice repos.

IEC 62304 Considerations 🔗

IEC 62304 establishes the software life-cycle framework but doesn't dictate how finely you decompose your architecture. It defines a software item broadly as "any identifiable part of a computer program" and a software unit as the level not further decomposed. These can be logical or physical—manufacturers choose decomposition that fits their product and risk.

It's acceptable (and often preferable) to document a conceptual decomposition for reviewer comprehension, as long as you keep names consistent and maintain traceability.

Traceability Over 1:1 Mapping (FDA GPSV 2002) 🔗

FDA's General Principles of Software Validation explains that the Software Design Specification (SDS) may include both a high-level summary and detailed design information to reach different audiences. It emphasizes traceability analysis—linking design to requirements and source code/tests to design—rather than enforcing structural mirroring between documents and code.

Reviewers need to follow the thread: intended use and hazards → requirements → design elements (e.g., system items) → verification/validation evidence. Provide that thread clearly and you've met the expectation, even if your repository layout differs.

Misinterpretation Alert: “The Design Constrains the Programmer” 🔗

You might encounter this line in FDA’s General Principles of Software Validation (2002):

This statement might seem to require that design elements strictly mirror source code—but that's not what FDA intended.

FDA is emphasizing control of design intent, not one-to-one structural equivalence. The design specification should be complete enough that developers don't have to invent new features or reinterpret ambiguous requirements. However, the conceptual structure of your design doesn't need to match the physical structure of your code.

Later in the same guidance, FDA clarifies that traceability "may include" relationships among requirements, design, code, and test cases. That "may include" is deliberate—it allows flexibility, provided the logical links between requirements, design, and verification are clear.

Bottom line: FDA wants developers to follow the design's intent, not replicate its diagrammatic structure in code. Traceability and intent alignment are mandatory; one-to-one mapping is not.

How to Write Your Next Submission 🔗

- Show a clean, labeled, architectural diagram overview first: Start with one high-level diagram that names major modules/layers, their key interfaces, and data flows. Use consistent icons and line styles, and add short annotations that cross-reference requirements or design IDs.

-

Follow with supporting views, as needed:

- Data-flow or sequence diagrams for safety-critical paths

- Cybersecurity architecture views (interfaces, trust boundaries), required for cyber devices.

- A deployment/ops view for cloud SaMD (where the device boundary lives)

- Make traceability effortless: Provide a table that maps requirements (SRS) → system items (SDS) → testing (V&V) (and, if helpful, code references).

- Name things consistently: Use consistent terminology and names across all diagrams, SRS, SDS, and tests, and avoid undefined acronyms.

- Keep SDS lean but sufficient: Your SDS can mix high-level and detailed content—include just enough to show how design fully and correctly implements the SRS and safety controls. And remember, a SDS document is not usually recommended (or required) by FDA for Basic Level Documentation software.

Bottom Line 🔗

In practice, FDA reviewers expect submissions to show logical consistency and traceability, linking requirements, design elements, and verification activities in a clear, reviewable manner. They do not expect the design documentation to mirror the internal structure of the codebase. Maintaining this separation between conceptual design and physical implementation allows teams to focus on what truly matters for regulatory review: demonstrating that the software’s architecture supports its intended use and mitigates risk effectively.